Unreliable information is hurting the global effort to defeat the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic. A surge in false information has created the perfect storm for cybercrime and spreading harmful falsehoods. The increase of misinformation and disinformation during a health emergency hamper an effective public health response while sowing confusion and distrust. To combat this crisis, international collaboration is essential, while citizens must understand the key terms in the uphill battle against the rise of false information.

Coronavirus has created the perfect storm for waves of false information to travel across the globe. Combining unprecedented factors such as a global pandemic, floundering economies, restrictive measures like government-mandated lockdowns, social distancing, and extreme anxiety has led more people online to search for answers, rational reasoning, and relief. Through it all, many people have become predisposed to interpret events and information in whatever way is most attractive as an explanation for these undesirable circumstances.

Misinformation and disinformation

The World Health Organization (WHO) recently stated that incorrect information “spreads faster and more easily than this virus”, extending beyond borders and causing a universal flood of falsehoods. But an excessive amount of information around an issue can make it difficult to identify fact from fiction. To combat this tendency, false information must be distinguished and categorised. Misinformation often happens when false information is produced or shared innocently, without the intent to deceive. Conversely, disinformation is false information that is produced or shared with the purpose of deceiving. The spread of both forms during a public health crisis disrupts effective emergency responses and sows confusion and distrust.

Consequences

The consequences of false information, such as blaming the emergence of coronavirus on the wrong source or doubting its seriousness, can be life-threatening on a massive scale. When the novel coronavirus was emerging, hoaxes and conspiracy theories about the origins of the virus were circulated, including allegations that it was linked to 5G networks or to HIV. These false claims have been corrected by the scientific community, but many of the public remain persistent in their pursuit for quick, tantalising claims.

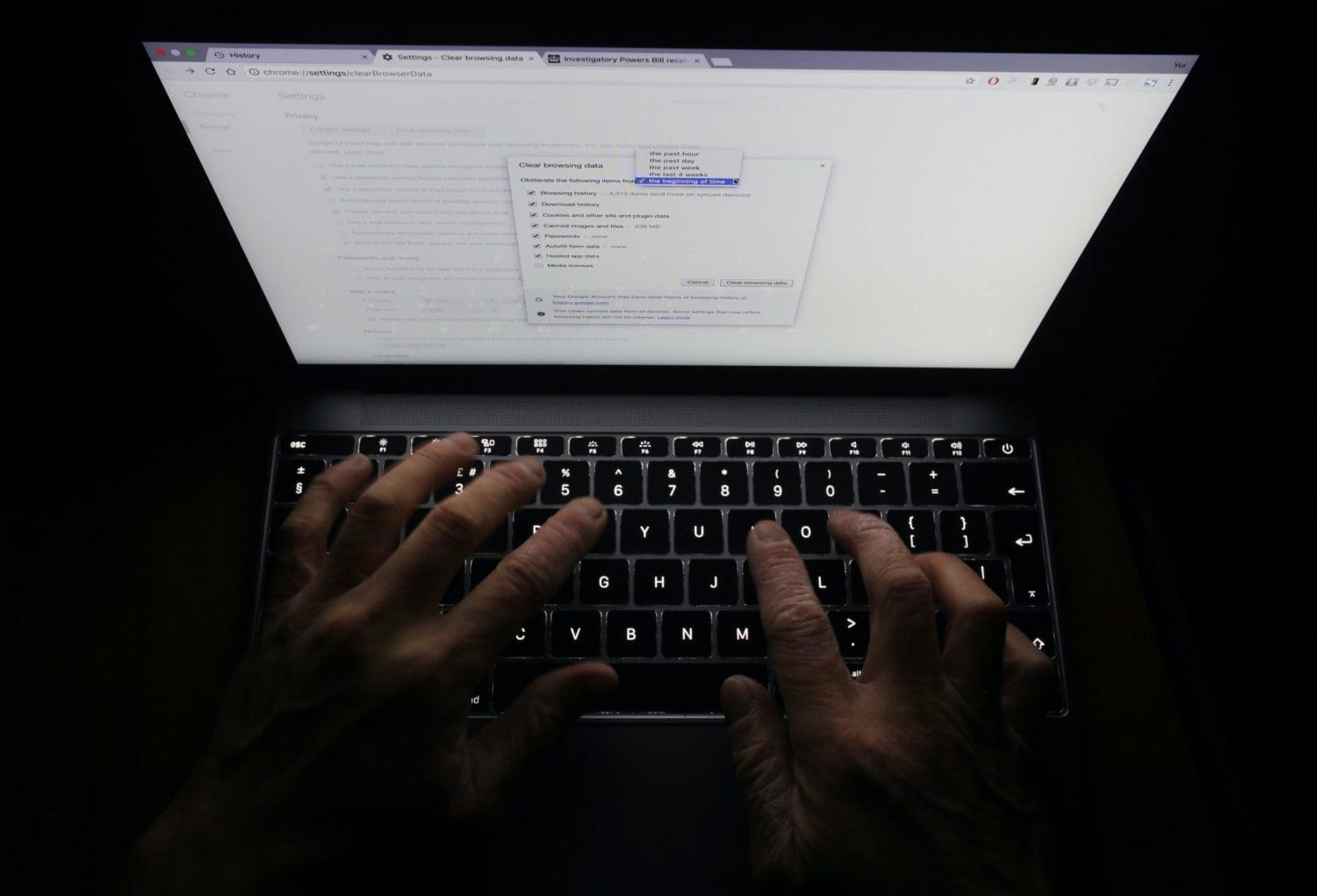

Propaganda, self-interest, and trading false information are deep-seated practices that date back through human history. In pre-internet days, these campaigns were more likely to stay within regional boundaries or move slowly; now, they can spread like a wildfire with large-scale traction. The rise of technology and social media platforms in the digital age has exacerbated these risks. While the internet and social media platforms make spreading ideas easier and more efficient, the internet is merely a tool for human interaction.

We want to believe

Our interactions on digital platforms have deep roots in our psychology. If an individual searches online via a platform such as Google, they are likely to find various dubious websites to confirm their beliefs. Search engines often point users to the most sensationalist information available. Hence, people more easily absorb the information that is close at hand, rather than less accessible but more reliable content.

According to a report in the scientific journal Science, false news is 70% more likely to be retweeted than true news stories. And conspiracies tend to be more popular than scientific news itself. But simply dismissing conspiracy theorists with mockery has proven to lead to further vindication and polarising effects.

Studies have shown that people want to believe that their group or inner circle is correct and good-natured, which often pairs with viewing outsiders’ opinions and beliefs as wrong. Individuals tend to view information and ideas from and through a partisan lens, which can form echo chambers. Within an echo chamber, every new piece of information will find a way to fit the paradigm. When people seek information, they find it from places that cater to their beliefs. And they may build a community around their beliefs that makes them feel like those in the group are the ones who have figured out the truth. Therefore in the current climate, sources offering careful analysis and opinions from experts or professionals are often met with distrust or disdain, while outlandish claims are readily embraced.

Finding the truth

Individuals must learn how to tell a trustworthy source from a non-trustworthy one, taking a default position of skepticism. Society must scrutinise its beliefs and rationales to distinguish between the ridiculous and the reasonable. Enacting this change will require a challenging re-education of thinking across generations.

So, how do we find truth in a post-truth world? To minimise the spread of false information, governments, NGOs, media, corporations, scientific bodies, and individuals must be prepared to act when information is evidently false. International collaboration is essential in combating false information. We must work together, viewing each other as partners rather than competitors in the spreading and sharing of accurate information. Transparency, credible sources, and media-technology literacy are vital tools against false information, an ever-evolving problem that we cannot fight only on the individual level.

Find out more about the issues raised in the article in this film.

Featured image via pxfuel