People in lockdown Britain find ourselves living in a ‘state of exception’ – the expansion of the state’s emergency powers and suspension of rights in the name of public safety. For at least the next six months, and for up to two years, many fundamental freedoms have effectively been abolished, with little scrutiny by parliament.

This extremely authoritarian response by Boris Johnson’s government comes after it was dragged reluctantly to enact physical distancing, self-isolation, and shielding the most vulnerable people in society from infection; essential measures enacted by public anger at policies that seemed out of step with those of other countries. Ministers had seemed far more interested in protecting the financial markets than in protecting people.

Now many of us, apart from NHS staff and key workers, are stuck at home, effectively under curfew, anxiously worrying about our loved ones and wondering what happens next.

It seems inevitable that the government is also starting to ask itself the question: what happens when we finally emerge from a crisis that has fundamentally challenged how our society is currently structured?

Police units more concerned with security than human rights

For decades, there have been many social and political movements which were already rejecting different aspects of capitalism’s priorities and arguing that ‘another world is possible’. As a result, they have faced years of unwarranted attention and intensive surveillance by counter-terrorism police that continues to this day.

As the Network for Police Monitoring (Netpol) has repeatedly highlighted, secret decisions about who is considered a risk or a threat, and thus, who is labelled an “extremist”, are made by police units concerned more about security and defending public order than about human rights or protecting the environment.

As documents released earlier this year show, just having an “anti-establishment philosophy” is enough for the police to classify individuals as a potential threat. Even in ‘normal’ times, counter-terrorism policing’s obsession with hunting for “extremists” in every conceivable social movement seems hard to comprehend, but these are now far from normal times.

It’s hard to imagine the police’s search for “threats” has suddenly ended, especially when people are questioning not only the government’s response to the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic but also the decisions that led to a decade of austerity that undermined our public services. How is there suddenly funding to fix societal issues, at least in the short term, that before we were told were insurmountable?

Organising under lockdown

Our current lack of freedom of movement means there’s no demonstrations, marches, occupations, or most other forms of direct action. But people are still protesting – from banner drops to petitions – and organisations are still seeking to apply pressure on the government where they can. There is a huge new network of mutual aid groups offering support to their neighbours. Unable to organise anywhere else, campaigners are all mobilising online.

Yet, as the recent Independent Office for Police Conduct report on the deliberate shredding of Metropolitan Police intelligence documents again reminded us, most police surveillance relies on open sources such as social media to build profiles on individuals and organisations, rather than covert methods or undercover officers.

Right now, campaigners’ dependence on relatively insecure, often very public means of communication – Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, Zoom – makes on-line organising vulnerable to routine data-driven police surveillance.

Mutual aid or domestic extremism?

Furthermore, as Netpol pointed out last year, one of the five paranoid reasons why the police are more likely to categorise you as a “domestic extremist” is that, like local groups offering mutual aid, you are part of a campaign or movement that is new or emerging. The very fact that these groups are providing a direct alternative to what’s offered by the state means the police are likely to be monitoring them under the guise of domestic extremism.

There is, therefore, understandable alarm that emergency powers will lead to further restrictions on civil liberties and the strengthening of Britain’s surveillance society once the crisis starts to recede. However, it may also lead to sustained political challenges to the status quo that the government and the police – particularly its “extremism” intelligence-gatherers – will want to undermine and disrupt.

That is why now, when our civil rights may seem so much less important than protecting public health, campaigners must think about what happens when we eventually emerge from lockdown.

It is reasonable to assume the state will once again view any demands for significant changes to society, this time as a consequence of the coronavirus pandemic, as a threat from “extremists”. That is why we still need to demand that the police stop categorising campaigning and protest activities as ‘extremism’.

Political campaigners are not terrorists. Whatever else changes, that remains as true as it was before a virus turned the world upside down.

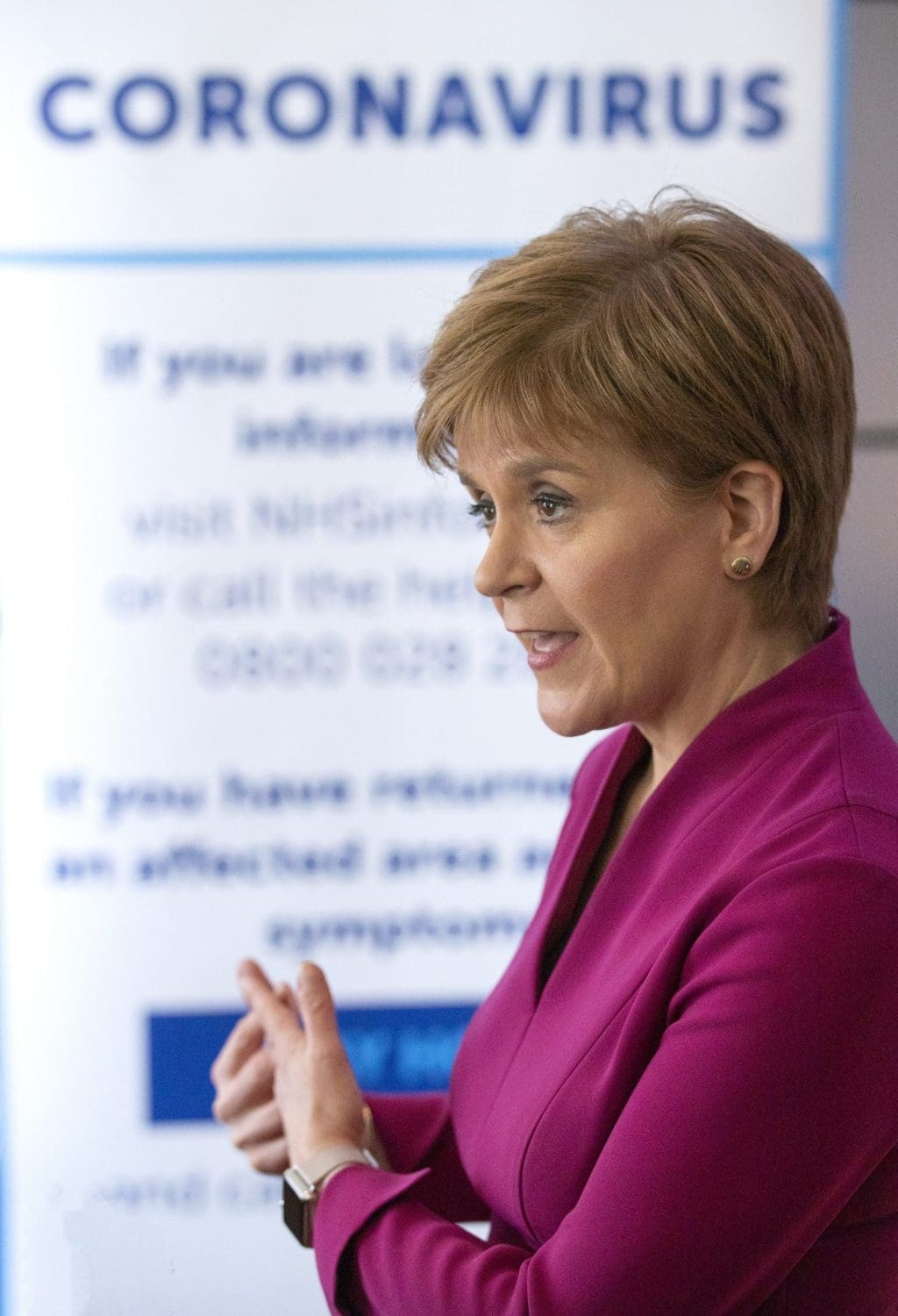

Featured image via Emily Apple