Two World Health Organisation (WHO) experts will spend 11-12 July in Beijing to lay the groundwork for a larger mission to investigate the origins of the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic.

One animal health expert and one epidemiologist will work to fix the “scope and terms of reference” for the future mission. It will be aimed at learning how the virus jumped from animals to humans, WHO’s statement said on 10 July.

Origins

Scientists believe the virus may have originated in bats. It was then transmitted through another mammal such as a civet cat or pangolin before being passed on to people at a fresh food market in the central Chinese city of Wuhan in late 2019.

In an effort to block future outbreaks, China has cracked down on the wildlife trade and closed some wet markets. It has also enforced strict containment measures that appear to have virtually stopped new local infections.

Politically sensitive

The WHO mission is politically sensitive, with the US, the top funder of the UN body, moving to cut ties with it over allegations the agency mishandled the outbreak and is biased toward China.

More than 120 nations called for an investigation into the origins of the virus at the World Health Assembly in May 2020.

#COVID19 has taken so much from us. Its magnitude has touched virtually everyone in the world and clearly deserves a commensurate evaluation, which is also giving us an opportunity to break with the past and build back better.

— Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus (@DrTedros) July 9, 2020

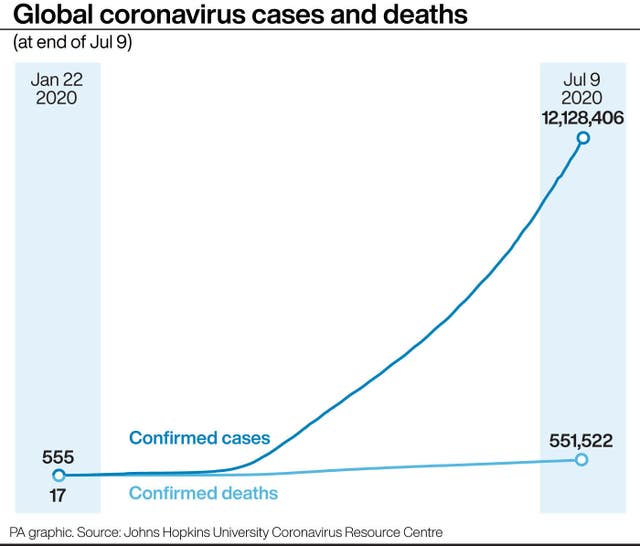

China has insisted that WHO lead the investigation and for it to wait until the pandemic is brought under control. The US, Brazil and India are continuing to see an increasing number of cases.

Armed police stand guard outside a testing site for China’s national college entrance examinations, also known as the gaokao, in Wuhan in central China’s Hubei Province (AP)

Lack of transparency

The last WHO coronavirus-specific mission to China was in February 2020. Following the mission, the team’s leader, Canadian doctor Bruce Aylward, praised China’s containment efforts and information-sharing. Canadian and American officials have since criticised Aylward as being too lenient on China.

An Associated Press investigation showed that in January, WHO officials were privately frustrated over the lack of transparency and access in China. This is according to internal audio recordings. Complaints included that China delayed releasing the genetic map, or genome, of the virus for more than a week after three different government labs had fully decoded the information.

Privately, top WHO leaders complained in meetings in the week of 6 January. Complaints suggested China wasn’t sharing enough data to assess how effectively the virus spread between people, or what risk it posed to the rest of the world. This lack of transparency cost valuable time in learning how to deal with the virus and control its spread.