A couple of decades ago all mass communication was one-sided. To newspapers, radio and television, the ‘audience’ were simple recipients of information. All that changed with the advent of the internet, online comments and social media. Finally, that ‘audience’ was given a voice, was entitled to have an opinion and express it. A world of possibilities opened up. A dialogue between those who create content and those who consume it was suddenly possible. The only problem was that along with the engagement in these constructive conversations came the opportunity to insult without fear of retaliation.

Sadly, the internet has become a sort of reckless Wild West where many concepts and ideologies that we believed were overcome, dead or agonising, are re-emerging. Behaviours that poison the atmosphere range from ill-manners to hate speech. As Danielle Keats Citron states in her book “Hate crimes in cyberspace“, the internet has become “the next battleground for civil rights”.

No comment

The trend among internet outlets is to eliminate the comment sections. One of the reasons invoked is that, with most of the discussion taking place in the social media, the comments section is no longer needed. However, there are other causes.

One of the first sites to remove the comments was Popular Science, arguing that comments can skew the reader’s perception of a story and undermine the integrity of the science. They cited a study in which participants were given a scientific text describing a fictitious new technology with potential benefits and risks, and asked to give their opinion. Before passing their verdict, though, half of the participants were exposed to rude comments while the other half was shown comments written in a more civil tone. Those who were initially supportive or dismissive of the new technology (identified by preliminary survey questions) felt the same way after reading the civil comments. However, exposing readers to rude comments increased their concerns on the risks of the new technology, despite the fact that in both cases the comments were evenly split in favour and against it. One of the conclusions was that

Much in the same way that watching uncivil politicians argue on television causes polarization among individuals, impolite and incensed blog comments can polarize online users.

But probably the main reason why comments are being banned from sites is that it has become difficult (and expensive) to moderate them, as racism, sexism and homophobia tend to flourish in this section. A recent analysis in The Guardian found that the main targets of abusive comments were women and black men, despite the fact that the majority of their opinion writers are white men. And it is probably not a coincidence that the most harassed writer turned out to be Jessica Valenti, a journalist who writes about feminism and gender issues.

Why

Arguably, anonymity is the most important element associated with online aggression. Few people would say, face to face, some of the things that we read on the internet. Studies of adolescents and young adults have found that people that become uncivil online do it, at least in part, because they feel confident that they will not get caught. Anonymity also induces a psychological effect termed “deindividuation“, whereby we perceive ourselves and others as part of groups, diminishing both our inner restraints and our empathy.

The feeling of group belonging is especially strong on social media and induces what psychologists call “diffusion of responsibility“, by which we become less responsible for our actions. Also, we often have the impression of being surrounded by people that endorse our own point of view and this can prompt us to express ourselves in an impolite or aggressive way, sometimes in an unconscious search for agreement from others in our network.

Although anyone, fostered by anonymity, has the potential to become an online hater, there seems to be a certain predisposition towards this kind of behaviour. A 2013 study found that people are roughly split into those who have a tendency to like things in general and those who are more prone to dislike them. In the words of one of the researchers:

Some people are more prone to focusing on positive features and other on negative features.

Similarly, another study showed a high correlation between trolling – acting in a deceptive, disruptive or destructive way online – and personality traits such as narcissism, psychopathy, and sadism.

It has consequences

While those who insult or promote hate speech might suffer from “deindividuation”, that is not the case for the victims of their words. Dealing with these kinds of comments can be hard and stressful. As Jessica Valenti puts it in her article about being the most harassed writer on The Guardian:

Imagine showing up to work just to run the gauntlet of hundreds of people telling you how worthless you are.

Many other content creators have expressed similar views: While they know these opinions are ill-intentioned and belong to a minority, it is not easy to ignore them. Anyone who has ever put some effort into creating something knows how painful it is to see it destructively dismissed.

This lack of empathy could also be enabled by the way we use the internet. According to the one percent rule, for any given online community, only one percent of its users create content. In wikis and other collaborative sites, another nine percent contribute by editing some of this content. This means that most of us usually act as information consumers or, in internet slang, ‘lurkers’. A few examples illustrate this idea: There are ‘only’ 150m blogs out of more than 3bn internet users, which gives a figure of around 0.05 blogs per user. And despite receiving over 350m visits every month, Wikipedia has a mere 70,000 active contributors, meaning that for every person that contributes there are 5,000 than lurk.

But the problem is not only about creating content, but getting it seen. The impact of our words in the social media is usually small and on platforms such as Twitter, it can be almost meaningless. According to a 2013 report, the median active Twitter account has 61 followers, while only 10% of accounts have more than 458 followers.

So perhaps if we had to face the experience of having our work judged by a larger audience we would think twice before writing a harsh comment.

Troll Hunters

Is there something that can be done?

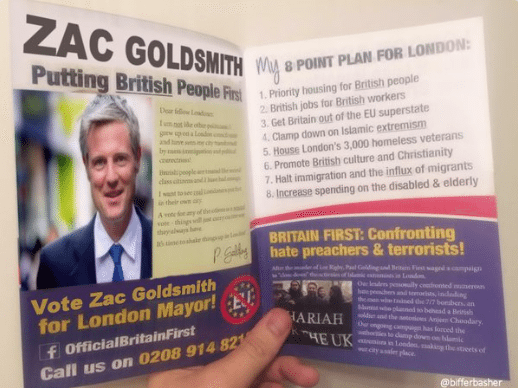

Since anonymity seems to be the cornerstone of online hate, some people believe that we shouldn’t be allowed to post anything anonymously. A study that analysed comments on articles about immigration found that they were more likely to be uncivil when newspapers allowed users to remain nameless.

The problem is that anonymity is also a fundamental part of the internet. It allows whistleblowers to expose illegal or unethical activities without fear of retaliation. It gives people the chance to express themselves freely when seeking advice or stating political views that are not endorsed by their social circle. All in all, anonymity is crucial to anyone who doesn’t want a particular aspect of their lives to show on an online search.

But when people hide behind pseudonyms to hurt others, some believe that is fair game to track them and face them with their actions. That’s the rationale behind Troll Hunters, a Swedish TV show where online bullies are exposed. Conducted by national TV legend Robert Aschberg, the program shows that online haters are in fact a heterogeneous bunch, from old ladies to kids. Their reactions when outed are also mixed: while some burst into tears, others deny the accusations, try to flee, or become aggressive.

But exposing wrongdoers doesn’t make the problem go away. Following the outing of Reddit troll “violentacrez”, who managed online forums that contained all sorts of creepy material (including pictures of sexualised underaged girls and photographs of women taken surreptitiously), a debate on the ethics of the exposé was sparked. Commentator Sady Doyle deemed this kind of outing as “sensationalist” and urged the need for structural changes. In her own words:

Ending bigotry and sexual harassment is not as simple as selectively unmasking one or two perpetrators. It relies on all of us working daily to create a culture in which such behaviours aren’t tolerated.

Others, including Yishan Wong, CEO of Reddit, where the forums were held, appealed to freedom of speech to criticize “doxxing” (the internet slang for outing) and justified their decision for not removing the offensive material on the basis that it was not illegal.

The problem is that, ironically, what happens when you expose people that bully, harass and spread hate is that they become targets of bullying, harassment and hate from others. Not only that, but there is always the risk of exposing the wrong person.

Finding a way to conciliate the freedoms of speech and anonymity won’t be easy. In the meantime, perhaps it would be wise to follow the old internet mantra: Don’t feed the troll.

Featured image via Flickr/Jan Hammershaug