Medics across Britain have risen to unprecedented challenges during the nation’s first 100 days in lockdown.

Frontline workers have been seen as coronavirus (Covid-19) superheroes by members of the general public and were applauded for their efforts every Thursday at 8pm for the first 10 weeks of the crisis.

While people have faced restrictions on their movement and social lives, here four doctors from the British Medical Association (BMA) describe their experiences during the last 100 days for the PA news agency.

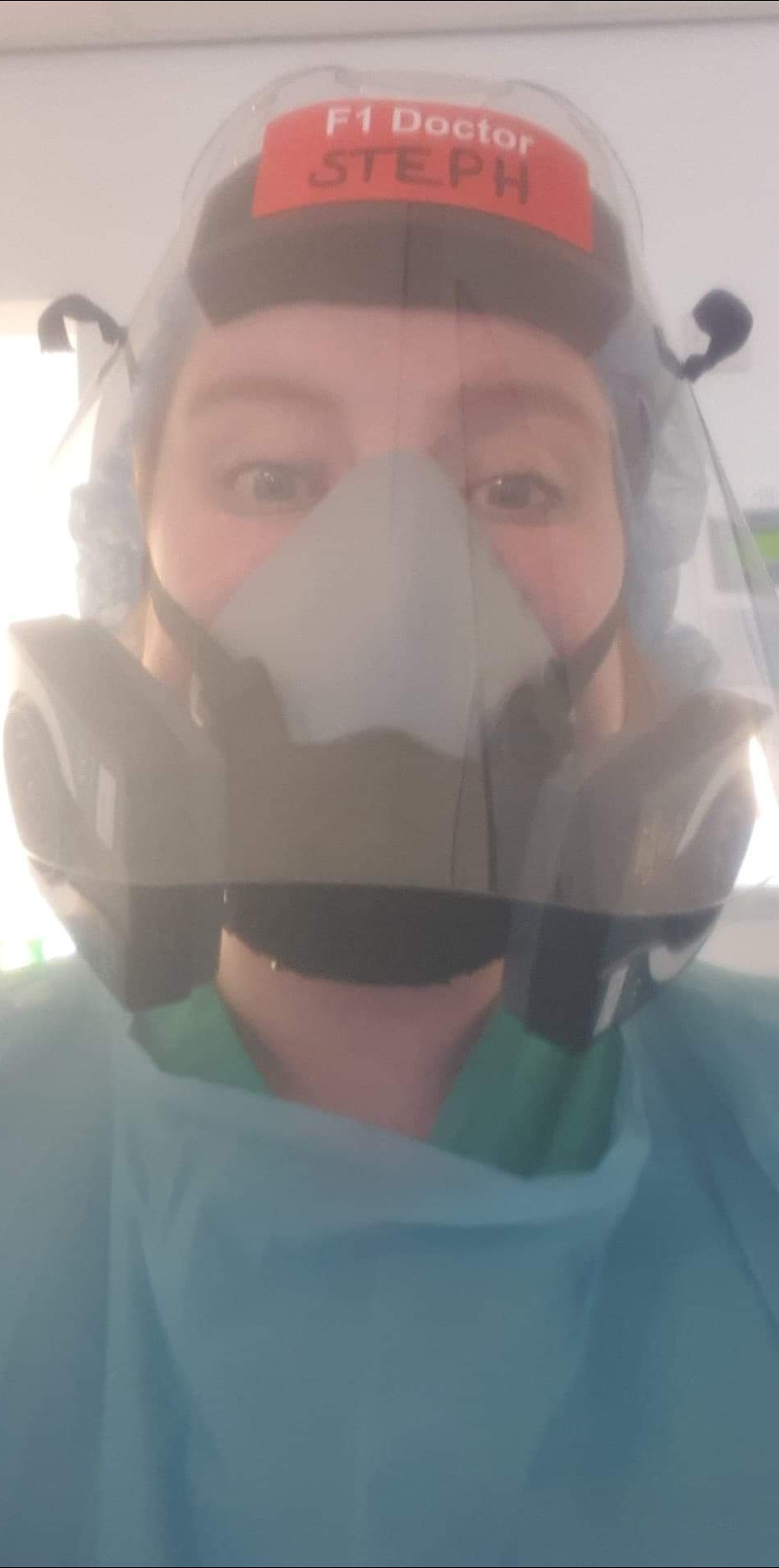

– Stephanie Rees, a junior doctor at Glan Clwyd Hospital in north Wales, said seeing a patient die without their loved ones at their bedside was a “hard moment”

“I’m what you would call a ‘hugger’. Passed an exam? Hug for you. Successfully placed a cannula? Hug for you,” said the BMA Wales junior doctor committee member.

“Early on, when social distancing was just being introduced, a friend of mine passed their degree and officially became a registered nurse, so what was my first reaction? A faux pas – I hugged her, and she recoiled away from me – clearly not the reaction I was going for.

“Masks and PPE isolate us from not only our patients, but also our colleagues.”

On families being able to visit patients, she added: “A quick video call is no replacement for holding their hand.”

“I can’t imagine what it would be like to have a loved one in intensive care, not be able to visit, and only get one or two phone calls a day updating me,” she said.

“The hardest part is when these conversations are not good news. When we think a patient has deteriorated to the point where there is nothing more we can do, we invite one to two family members into the unit to visit them and say goodbye, but what do we do if their relative is shielding or vulnerable? We can’t in good conscience recommend coming into the Covid section of intensive care, no matter the amount of PPE we provide them.”

Dr Rees added: “One of my hardest moments was when a patient passed away without their family with them. The last time they saw them was when they were admitted to hospital. Two nurses sat with the patient the whole time, holding their hand and playing the music they enjoyed.

“This time has brought with it some of my hardest moments as a doctor, but it has also brought some of the most heartwarming.

“One of our patients had their birthday, and we managed to get their close family and friends together to do a video chat of them opening their cards that had been delivered to their unit. It was such a small thing for us to do, but it meant so much to the patient and their family.”

– Dr David Wrigley, Lancashire GP and deputy chair of the BMA Council said he hopes a silver lining of the crisis will be a reduction in red tape for doctors.

“The way I deliver care has shifted drastically over the past three months from the usual face to face surgeries, to telephone and video consultations in order to make care safer for NHS staff and patients,” he said.

“One small silver lining of these past 100 days has been the reduction in box ticking, which has allowed us to focus more of our time on patient care.

“I hope that, in the future, the NHS will thoroughly investigate how processes can be simplified, so that doctors can spend more time with patients, as opposed to this bureaucracy and paperwork.

“Working closer with colleagues has fostered a greater sense of camaraderie as we’ve had to deal with various issues such as PPE (personal protective equipment) shortages and handling a very serious pandemic right on our doorstep.

“For many, this has also been a challenge as a large number of doctors have not yet had any time off and their mental health has therefore suffered as a result.”

– Dr Rebecca Acres, chair of the BMA East Midlands regional council, said that seeing patients leave intensive care in full health “makes all the hardship worthwhile”.

“The past 100 days have been a steep learning curve for me as I was redeployed at the very beginning from theatre anaesthetics to intensive care.

“While we’ve probably seen fewer patients over this period, they have been much more unwell than in pre-Covid times. The mortality rate has been four times as high, while patients who are critically unwell remain so for a much longer time – in some cases six weeks or more before recovering fully.

“It’s been a trying period for staff as well as patients. We have had to spend all of our working time in full protective equipment, meaning that communication amongst teams becomes very difficult and comforting colleagues after a hard day is also a challenge.

“Over the past 100 days, we’ve seen just over 50 patients leave intensive care having made a full recovery. Watching them come back to full health and leave makes all of the hardship worthwhile.

“We keep referring to ‘after’ in my unit. That time when we can hug our families, go on holiday, hang around in houses with friends, touch patients without full protective gear, talk to relatives without masks on and so on. It seems a while away yet, but I’m so looking forward to it.”

– Dr George Gardiner, a member of the BMA Northern Ireland consultants committee and clinical director for the intensive care unit in Belfast’s City and Mater Hospitals, who also became clinical director of the Nightingale hospital in Belfast, said: “As it turned out, the outcomes were much better than we had feared”.

On his experience in Nightingale he said: “We expected and planned for many more patients than we received, though briefly the admission rate seemed to be rising faster than we could mobilise staff and open beds.

“My colleagues succeeded in preparing clinical areas for use as intensive care and preparing staff from other areas to work within it.

“Their efforts in the few weeks before the patients started to arrive were truly remarkable – approximately 1,000 staff from all disciplines had an induction to critical care in some form, and 78 beds were ready to take patients with more in reserve.

“I think we all expected the mortality to be high and the work to be exhausting. As it turned out, the outcomes were much better than we had feared but the levels of delirium and burden of multiple organ failure was much higher.

“The high points have got to be watching patients finally leave ICU after prolonged stays, working with colleagues who were entirely out of their comfort zone yet enthusiastic and focused, and finally getting out of PPE.”