As the festive season winds down, there are three things we could have predicted with near certainty. Parents were exhorted to spend ever larger sums of money as a way of putting a price on their love for their children. The police caught an alarming number of drink drivers. And demand at hospital accident and emergency (A&E) departments was apparently unprecedented. But while this latter statement could merely be a harmless case of a journalist reaching for a suitably evocative adjective, it is in fact nothing of the sort. The NHS crisis has been manufactured by a policy of under-resourcing the health service. And then scapegoating it while it inevitably struggles to fulfil its purpose.

Describing demand at our emergency departments as unprecedented does more than conjure an image of patients and physicians in crisis; it is a linguistic cleansing agent. It absolves the people who allocate resources to our medical services of any responsibility for those harmed in the process. This happens because it encourages the idea that if demand had merely been ‘precedented’ rather than ‘unprecedented’, then those providing emergency medicine would not have been forced to their knees by the afflicted tide of humanity thoughtlessly thronging through the doors.

Blame culture

In other words, say the ministers, if you’re looking for someone to blame in a crisis, don’t blame the government. We were caught by surprise. Blame yourself. Blame the patient.

But there certainly is reason to point the finger.

Figures from The Royal College of Emergency Medicine’s Winter Flow Project puts nationwide performance against the Four Hour Standard at Type 1 emergency departments (ED) at no more than 78%, and falling. The NHS Constitution states that 95% of patients should expect “a maximum four-hour wait in A&E from arrival to admission, transfer or discharge”. Four Hour Standard performance is now at levels that Conservative MPs have previously condemned in Wales as part of broader efforts to paint Offa’s Dyke as the line between life and death.

Of course, if more patients turn up at an emergency department than ever before, that might come as a surprise. But only to people who know nothing about the subject, or are engaged in a wilful refusal to grasp reality. Even without examining the issue with hard data – as we will below – if demand has also been described as ‘unprecedented’ in almost every year for more than a decade, there’s obviously a fair probability that demand might rise to ‘unprecedented’ levels this year as well.

The numbers tell the story

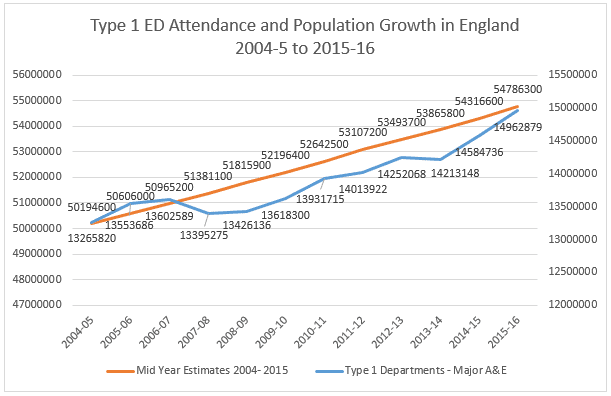

Probability then hardens into certainty when you realise that levels of A&E attendance and population growth are intrinsically linked [pdf]. Here, for example, is what A&E attendance and population growth in England look like on a chart when presented together:

What this shows is that, as the number of people has steadily increased, so has the number of patients. Nor is it necessary to interfere with the data to make these factors look so closely related. Since 2004, the UK population has increased by 9.15%. In the same period, the number of Type 1 ED attendances has increased by 12.79%. To put it another way, in 2004-5 there was one Type 1 ED attendance per 3.78 members of the population. In 2015-16, that ratio was one for every 3.66 members of the population.

In short, it defies logic to claim, as the population grows and the average age increases, that a rise in demand for medical services has come as a surprise. Whatever the assorted word-jugglers and political spin doctors might like you to believe, if there are more people there will be more patients. And those patients’ expectations are no more unreasonable than they have ever been.

This is the sense of the advice [pdf] recently issued by NHS England under the catchy title of Transforming Urgent and Emergency Care Services in England. Safer Faster Better: good practice in delivering urgent and emergency care:

Emergency departments (EDs) should be resourced to practice an advanced model of care where the focus is on safe and effective assessment, treatment and onward care. While it is essential to manage demand on EDs, this should not detract from building capacity to deal with the demand faced, rather than the demand that is hoped-for.

Stretched too thin

Unfortunately, hospitals are struggling to cope with the most stringent period of financial austerity in the history of the NHS. But there is little sign that either the government, or any of Lord Lansley’s lamented quangos, are prepared to recognise this reality. At least in ways that mean providing more resources to deal with the problem. Instead, NHS Improvement has suggested that the way to solve the problem is to cancel almost all planned operations, in an effort to make more beds available.

As our emergency physicians have already pointed out, deciding not to treat one group of sick patients in order to treat another group of sick patients will not solve the problem:

Cancelling operations comes at a cost, and is no substitute for providing both more doctors in the ED and more beds for patients. This short-term measure to free up beds is unsustainable for both Trusts and patients.

The smear campaign

At the same time, those in the media and political sphere who want to ignore or hide this very simple reality have undertaken a smear campaign against the staff of the NHS itself. And against those millions of us who dare to request its services. This tactic is epitomised by the 10 January front page of The Daily Mail. Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt pulls an entirely false statistic out of thin air; an obliging press then prints it; the bloke in the pub complains about it, and so on.

This is the politics of desperation. A government that has consistently under-resourced the NHS and social care services, panicking in the face of the consequences. And anxious to pin the blame on anything but its own broken ideology.

What might indeed be unprecedented is if we properly resourced our hospitals so that they could care for the sick and the frail. Rather than pretending it would all be fine if only the patients went away. In this way, these entirely manufactured crises would become a thing of the past. And our healthcare system could continue its hard work of protecting and advancing public health.

Get Involved!

– Read more Canary articles on the NHS, and more from The Canary’s Health section.

– Support the Save Our NHS campaign, and other NHS campaigns.

Featured image via Twitter (original photo taken by Paul Fox on 27 May 2015 at the Royal Stoke University Hospital)