Ireland’s most senior drug official is embracing a revolutionary public health approach to drugs – he plans to decriminalise them. By making this bold move, resources will be put in place to support addicts in getting help for their condition, while still treating the sale and distribution of drugs as a crime.

According to reports in this week’s Irish Times, Aodhán Ó Ríordáin revealed plans to open up supervised injection facilities (SIFs) for heroin addicts, where users can obtain and use the drug — under strict medical supervision — away from criminal traffickers and dealers.

Mr O’Riordain hopes to add further centres in Cork, Galway and Limerick as part of his push to revolutionise the Catholic country’s anti-drug agenda.

“I am firmly of the view that there needs to be a cultural shift in how we regard substance misuse if we are to break this cycle and make a serious attempt to tackle drug and alcohol addiction,” the Irish Labour minister said, speaking at the London School of Economics this week.

These ‘injection centres’ will provide heroin addicts with clean needles and a safer closed, clinical environment with better access to health services; treating them as medical patients rather than criminals.

It would remain a crime to profit from either the sale or distribution of illegal drugs.

The UK’s only Green MP, Caroline Lucas, attempted to introduce SIFs to her Brighton constituency back in 2013, but was met with hard resistance from the Home Office.

Mike Trace, Chair of the International Drug Policy Consortium, led a commission looking into the feasibility of the development in Brighton.

“To get an officially recognised safe injecting room off the ground, you need your local police force to interpret a section of the Misuse of Drugs Act in a certain way,” Mr Trace said in a recent interview with VICE.

“The Home Office have consistently maintained the view that safe injecting rooms are contrary to the act, and there are no plans to amend it,” he added.

This stance is surprising when you consider the widespread administration of successful safe injection centres across Europe, with Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Luxembourg, Norway and Denmark already implementing them.

The continent’s move towards a more medicinal approach to drug addiction is powered by a growing body of medical evidence highlighting the effectiveness of treatment instead of punishment, as well as a changing public mood on the subject.

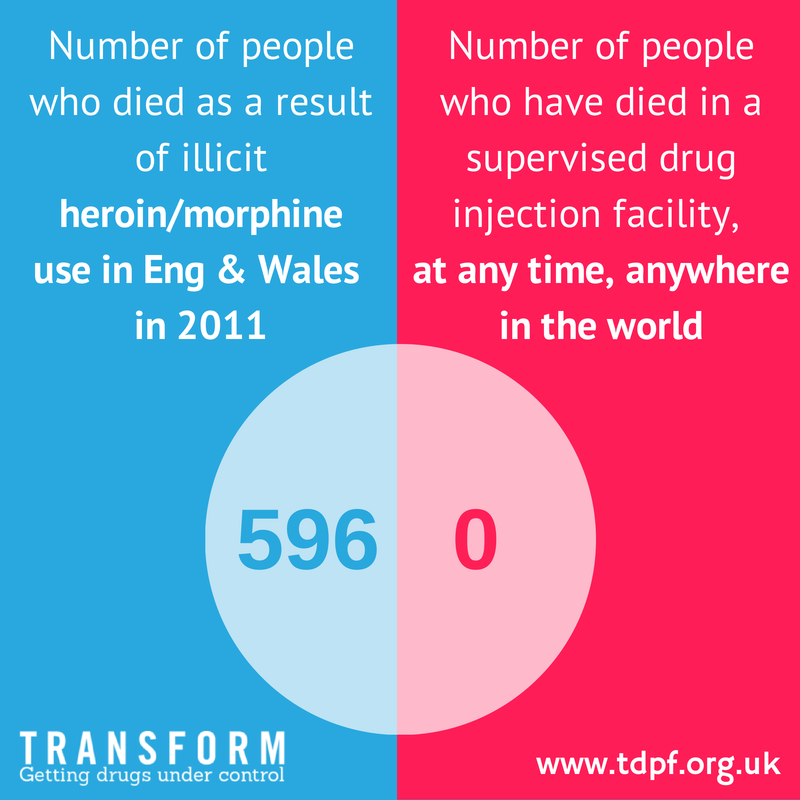

After all, safe injection sites have been found to lower the risk of contracting infectious diseases like HIV and Hepatitis C, thus easing the strain on medical services, while also reducing the number of dirty needles left on public streets.

An extensive study by the Drug Policy Modelling Program (DPMP) also found that SIFs make injecting practices less risky, improve access to drug treatment and care, and reduce crime.

The DPMP’s study, made up of 134 papers and reports, included one from a Sydney SIF where staff reported intervening in 329 overdoses in just one year, estimating that they saved 4 lives.

But David Cameron’s government isn’t open to helping addicts manage their condition in a way that is clearly successful elsewhere, even considering the fact that heroin/morphine related deaths in England and Wales increased by almost two thirds between 2012 and 2014, from 579 to 952, according to the latest figures from the Office of National Statistics – which would have the potential to lessen the impact of drug addition on our already overburdened NHS.

This trend clearly demonstrates the government’s failure in dealing with the country’s illegal drug problem. And yet no change is in sight, with the Prime Minister adamant that loosening drug laws is not the way forward.

“I don’t believe in decriminalising drugs that are illegal today,” Mr Cameron said is his last major announcement on the subject. “I’m a parent with three children; I don’t want to send out a message that somehow taking these drugs is OK or safe.”

However, you only have to look as far as Portugal to see how that may not be the message young people take from more lenient drug laws.

Lisbon officials decriminalised drug use and possession more than 15 years ago, leaving addicts in the care of the Ministry of Health rather than the handcuffs of the Ministry of Justice.

Since then the country has seen the “promising coincidence” of illegal drug consumption of 15-19 year olds drop. In the UK twice as many 16-24 year olds admitted to taking illicit drugs compared with the population as a whole.

And, while few expect a Conservative government to legalise all drugs, surely the evidence is strong enough to prompt a more open minded, medical approach towards those with serious addictions.

In Ireland, Aodhan O’Riordain has decided to look after some of the country’s most vulnerable people by offering severe addicts the chance to receive safe, secure treatment in his nation’s capital. He has also proposed the decriminalisation of small amounts of cannabis, cocaine and heroin.

His decisions have been based on much on the evidence discussed in this article, and he can only hope that whoever comes into power after Ireland’s elections next year supports his ideas.

In the UK, though, Caroline Lucas MP remains skeptical for the evolution of our illegal drug policies.

“This is a government that often says it wants to be guided by evidence and yet drug policy is more or less an evidence free zone,” she said.

But with record numbers dying and clear evidence supporting new techniques that increase mortality, surely it’s time the UK government dropped it’s antiquated, conservative standpoint, like Ireland, and started making drug policies based on fact rather than fiction.

![The next victim of NHS cuts? Cancer patients [VIDEO]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Screen-Shot-2015-11-04-at-12.37.50.png)