Director Ken Fero released his iconic film Injustice in 2001. It investigated the deaths of Black people in police custody in the UK. At the time of its release, police tried to silence the documentary and both the BBC and Channel 4 refused to show the film. Despite this, Injustice went on to receive the best documentary award at the annual Black Film-maker International Film Festival.

Ultraviolence is a vital follow-up film that has been 10 years in the making and premiered on 12 October. Produced as a visual letter written to Fero’s son, the compelling documentary shows even more police brutality, horror, and indignation. The #BLM cause continues to gain momentum across the world but is gradually given less media coverage every day. This film is the perfect reminder to everyone that Black Lives DO Matter and that racism DOES exist in the UK.

1. Repetition of “I can’t breathe”

“I can’t breathe” is becoming not only symbolic but also an exhausting and frightening phrase that we keep hearing as Black people are restrained and killed by the police. In Fero’s film, he notes that these were the exact same words spoken by Frank Ogburo seconds before he died in 2006. Ogburo, who was in London on holiday, struggled and pleaded for his life whilst being restrained by several officers on the ground. This uncomfortable, but very real, image of a police officer placing his knee on a human-being’s neck until he could no longer breathe really is a modern-day form of lynching.

Does this sound familiar? How many times must we suffer as Black lives are taken by the police and injustice is seared in our memory?

George Floyd’s excruciating death, which sparked global protests, is just one incident that many have argued is the result of a ‘US problem’ rather than an issue here in the UK.

But as the film highlights:

Since 1969, there have been over 2000 deaths in police custody in the UK.

And analysis from Inquest shows that:

People of black, Asian and minority ethnicity die disproportionately as a result of use of force or restraint by the police, raising serious questions of institutional racism as a contributory factor in their deaths.

The figures are stark:

- The proportion of BAME deaths in custody where restraint is a feature is over two times greater than it is in other deaths in custody

- The proportion of BAME deaths in custody where use of force is a feature is over two times greater than it is in other deaths in custody

- The proportion of BAME deaths in custody where mental health-related issues are a feature is nearly two times greater than it is in other deaths in custody

2. Activism and allyship is important

What does activism and allyship really mean? Writer Mireille Cassandra Harper’s “10 Steps To Non-Optical Allyship” guide is a good starting point.

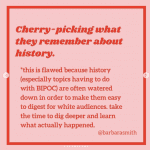

Fero’s skilful structure of historic archive footage, easy-to-follow explainers, and poetic analysis, capturing a mix of raw emotion but equally critical activism, is exactly what makes this documentary so impactful. Viewers are prompted to explore how the media can manipulate the truth and narrative of a story, how power structures influence racism, and how racism is embedded in Britain’s colonial history.

Yes, it’s difficult and uncomfortable to watch. A trigger warning is advised. It may prompt conversations about whether streaming the “undignified deaths that took place between 1995 to 2005” and showing these people’s last moments of life on screen is morally acceptable. But for Black people avoiding these kinds of issues and learning about the reality of what actually happens to Black people at the hands of the police is not a choice – even if it is disturbing to watch. Ultraviolence contains shocking but crucial evidence that exposes the wrongdoings of “beatings, shootings, teargassing, asphyxiation and neglect“. Here you’ll see the stories of the lives that have been affected and forever changed by systematic racism that not enough outlets have taken the time to broadcast.

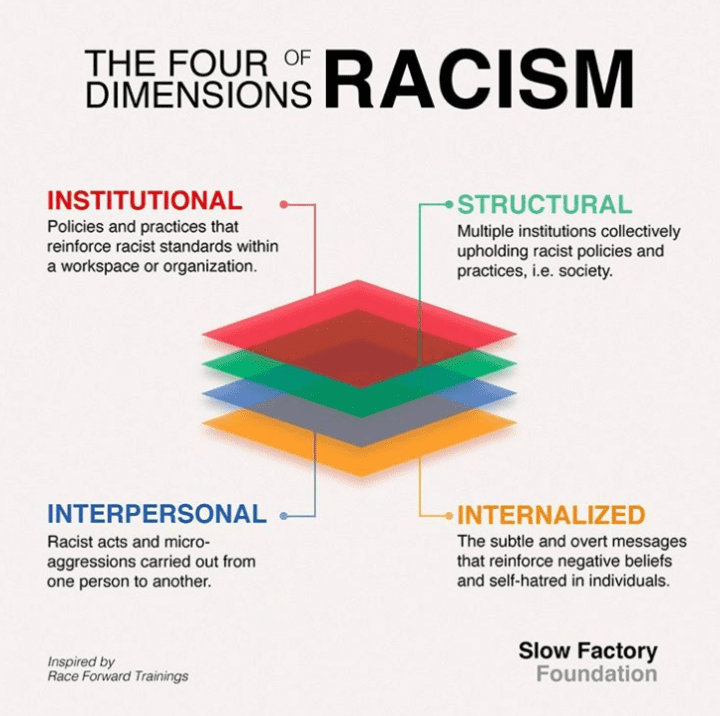

The Slow Factory Foundation highlights key points in which a person can identify four dimensions of racism:

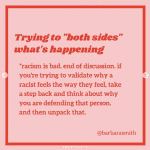

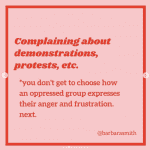

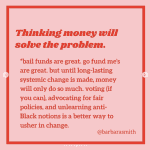

And if you decide to actively support people who are suffering from racism and discrimination in the UK, here are some helpful tips by Barbara Smith of what not to do as an ally:

3. The Endless Campaign

Joy Gardner, Frank Ogburo, Christopher Alder, Paul Coker, Brian Douglass, Jean Charles de Menezes, Roger Sylvester, Harry Stanley, Nuur Saeed, Mark Duggan, Jermaine Baker, Trevor Smith, Leon Briggs, Sheku Bayoh, Rashan Charles, and Kevin Clarke are only some of the victims’ names that we should know and remember.

Protests and demonstrations are key when demanding change from large institutional bodies, policymakers, and the government. It’s a critical tool used to grab the media’s attention and stress important issues on a global scale (to an extent considering media bias). Seeing the pain, distress, and determination of everyday citizens coming together to call for action against racism can result in a domino effect of great progression. But this isn’t always the case and there is always more to do. The steps taken after a protest are just important as the protest itself, and without a plan of action it can only achieve so much.

Standing up and speaking out can feel like a rollercoaster ride of optimism to make a change, but it can also become unbearable dealing with the aftereffects of when a cause’s momentum fizzles out in the media.

Not everyone acknowledges or recognises the trauma that people of colour face when they must constantly fight for an anti-racist society. Challenging the legal systems put in place in this country and the police that enforce them is a part of that burden.

The message in Ultraviolence is delivered clearly and calmly, but there is no denying that the call for “socio-political restructuring and revolution” is an adamant one.

4. Our justice system is broken

Following the lives of the families who have spent years grieving over their loved ones, being knocked back in the fight for justice and who still courageously protest today, illustrates a heroic and tiresome journey. Even though we don’t personally know these people, we are led to feel emotionally involved. We try to understand their agony and our natural human instinct influences us to feel the same anger and urge to stand up for those targeted by the unfair and unjust prosecution trials for those killed. It’s more than just witnessing horrendous killings and feeling empathetic. It’s war.

Christopher Alder, Jean Charles de Menezes, and Paul Coker’s deaths resonate throughout the film.

One of the most shocking evidence videos – if you can even compare the killings of individuals – shows Christopher Alder gasping on the floor in police custody for around 10 minutes as he is left to slowly die. Alder died in 1998. Despite a verdict of ‘unlawful killing‘ in 2000 – meaning someone is responsible for that person’s death based on evidence – charges of manslaughter brought against five officers were all dropped in June 2002.

15 years ago, Jean Charles de Menezes was shot seven times in the head by the Metropolitan Police at a London tube station. Mistaken as a terror suspect, de Menezes died in July 2005. Again, no officers were prosecuted for the killing.

The filming of Paul Coker’s girlfriend and family members is chilling, to say the least. Featured in the documentary, Lucy Chadwick, Coker’s girlfriend at the time, says that she heard Coker tell the police: “You are hurting me, I can’t breathe, you are killing me”. As Coker was taken into police custody, the film shows him lying on his front in his underwear, slightly twitching before he stops moving completely. Lying for 15 minutes alone, he was found and pronounced dead in August, 2005.

The inquest jury found that Coker had died from a cocaine intoxication and that a “lack of communication coupled with inadequate police training in identifying Coker’s condition as a medical emergency contributed to his death”. No officers were charged or prosecuted.

5. Are showing acts of police brutality helpful or harmful?

There are negatives and positives to streaming graphic videos that evidence police violence and brutality. Seeing Black people and other people of colour die on live streams and social media shouldn’t be a normality. Seeing this cycle of horror causes distress and trauma. It doesn’t necessarily address the issues of racism at hand and it can instead become a pattern of clicks, shares, and compassionate comments posted online. This doesn’t guarantee change. It can feel dehumanising and belittling to know that this may be the only reaction and response to another loss of life in police custody.

In Ultraviolence, Fero says:

Memory is fragile, and it needs to be spoken to be kept alive.

Without reflecting on these acts of brutality and learning from documented evidence, people could choose to be ignorant of the issues happening on our own doorstep. Or they may be aware of what has happened but might not feel obliged to address the problems because they’re not aired on their TV screens or regulated through their news outlets. Maybe people wouldn’t believe the incidents are true without video evidence. Racism is a worldwide problem and takes various forms in different countries. It’s a delicate subject to reflect on but an unavoidable topic.

Ultraviolence unforgivably forces us to address and learn from issues of racism, police brutality, and violence in the UK.

Featured image via Migrant Media/BFI London Film Festival