Stuart Christie, who died on 15 August 2020, was an anarchist revolutionary, author and prolific publisher, famed for his role in a 1964 attempt to assassinate fascist dictator General Franco. He was accused of being a member of the revolutionary ‘group’, the Angry Brigade, but acquitted on all charges. He also co-founded the Anarchist Black Cross, which provided relief and other support to anarchist prisoners.

I knew Stuart via our mutual friend Albert Meltzer, also an anarchist activist and publisher.

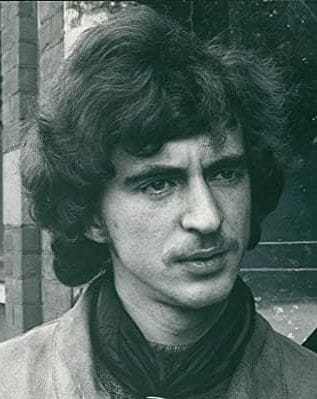

(The featured image above shows, left to right, Stuart Christie, Luis Edo, Albert Meltzer, Doris Ensinger.)

An adventure in Spain

In his youth, Stuart was involved with the Committee of 100, which campaigned against nuclear weapons. He helped with “research and direct action projects such as locating and publicising secret government shelters and military installations around central Scotland”.

At age 18, Stuart became involved in a different form of direct action – an attempt to assassinate the Spanish dictator and fascist General Franco. Stuart’s role was to take explosives from France into Spain. But the undercover police were waiting for him and he was arrested in Madrid before he could hand the devices over. He was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment and threatened with death by garotte. However international pressure, including support from Bertrand Russell and Jean-Paul Sartre, and wider public support, led to his release after only three years.

During those three years, Stuart associated with many revolutionaries jailed by Franco and on his return to the UK he, with Albert, decided to refound the Anarchist Black Cross and in the following year to publish Black Flag, its bulletin.

But Stuart soon attracted unwanted attention and, on 27 February 1968, the police raided his London home following an attack on the Greek embassy.

That followed a 21 August 1967 attack on the US embassy in London, which was strafed by machine-gun fire in protest at the imprisonment of Christie in Spain. That action was claimed by the First of May Group and later that year and in the years after more attacks claimed by the First of May Group followed (and not just in the UK). These include the Liverpool branch of the Bank of Spain, the Bank of Spain in London, the home of Tory MP Duncan Sandys, the Ulster Office in London, an army recruitment office in Brighton, the Imperial War Museum, the US embassy, a police station in Paddington, various Conservative Association offices, Lambeth court, army depots in London, the home of Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police John Waldron, two on the home of attorney general Peter Rawlinson, and the Italian Trade Centre in London.

In June 1970 Stuart’s home was again raided by police.

Angry Brigade

During the early 1970s, the Conservatives were in power under Edward Heath and there was widespread industrial action. It was a time of internment in the north of Ireland and in Scotland workers occupied the Clydeside shipyards. In the midst of this the Angry Brigade emerged, claiming more bombings, including a BBC van outside the Albert Hall during the Miss World contest, and offices of the Department of Employment and Productivity.

There was also another machine-gun attack, this time on the Spanish embassy. (It was later claimed in court that the gun used was the one also used in the August 1967 attack on the US embassy, so linking the Angry Brigade with the First of May Group.)

Guards were:

placed on Cabinet Ministers. These are angry times… Peter Walker (environment Minister), Melford Stevenson, Tory MP Hugh Fraser, Tory Prime Minister Heath and many others have received threatening calls. A communique sent to the Express newspaper says:

“THE ANGRY BRIGADE IS AFTER HEATH NOW. WE’RE GETTING CLOSER”.

Christie arrested

Meanwhile, London evening newspapers were “trumpeting from day to day about the ‘young Scottish anarchist recently returned from Spain’ whom they had branded as the most likely… people were disappearing off the streets for questioning”.

On 20 August 1971, several people were arrested after a raid by police on a flat at Amhurst Road, Stoke Newington. It was alleged that firearms, ammunition, explosives, and a ‘John Bull’ toy printing set were found. Also allegedly found were lists of properties owned by prominent politicians. The next day, police lay in wait in the flat and two people – Chris Bott and Stuart – turned up. They were immediately arrested. In all, eight people, including Stuart, were charged in relation to the Angry Brigade bombings. At the end of the trial four of the defendants – John Barker, Hilary Creek, Jim Greenfield, and Anna Mendelssohn – were found guilty, with each receiving a prison sentence of 10 years. The other defendants, including Stuart, were acquitted.

According to Major Yallop, who headed the Woolwich Arsenal laboratories, as well as the 25 bombings attributed to the Angry Brigade a further 1,075 bombings had come to his attention. Indeed, the bombing campaign continued throughout the remainder of 1971 and into 1972, well after the Angry Brigade arrests.

The wider context

Stuart went on to provide an introduction to Gordon Carr’s 1973 documentary on the Angry Brigade and the First of May Group actions. The first half of the documentary examines the context in Europe to the bombings. Perhaps the best quote in the film is from the Angry Brigade trial judge, who reportedly stated that the defendants had been “brought there [to court] by a warped sense of sociology”.

The documentary is followed by a second on the 1978/9 ‘Persons Unknown’ arrests and trial, which saw six people, including Black Cross activists, initially charged with conspiracy to cause explosions. But of those defendants who remained to plead their innocence, all were acquitted.

Publishing

After the Angry Brigade trial, Stuart thought it wise to avoid further police interest and so with his wife Brenda moved to Yorkshire and then to the Orkneys, where they set up Cienfuegos Press and later Refract Press. The Christies later returned to England, to Cambridge, where they continued their publishing activities,

In time, these publishing concerns led to an online bookstore: Christie Books, documenting via books, pamphlets, and videos etc, anarchist and other revolutionary struggles.

Solidarity

The essence of Stuart’s life was solidarity. I recall a situation when Albert found himself in trouble which demonstrates how, when Stuart’s global contacts were combined with the efforts of ‘ground troops’, solidarity got results.

Albert had been asked by a friend if a woman friend of his could stay at his flat for a while with her son. Albert agreed, though it was some months before she turned up. She explained to Albert that she believed (mistakenly) her son had been abused by his adopted parents. However, Albert was suspicious and it was not long before the newspapers had the boy on their front page, claiming he’d been kidnapped. Albert wasn’t sure what to do next and he and I arranged to meet up at a pub. There he explained the situation and we agreed to meet later at the Anarchist Bookfair while we thought about the next moves. But Albert didn’t turn up at the bookfair. (What I didn’t know is that his flat had been raided later that day and Albert and the woman arrested.)

I returned to Brixton and informed comrades what had happened. We had to be careful, as to aid a kidnapping was equivalent to conspiracy, with a hefty 15 years jail penalty. Nevertheless we drove to Albert’s flat in Lewisham, but it was clear no one was there. We then drove to Islington to see Gareth Pierce, Albert’s lawyer, and arrived just before midnight. Pierce rang Albert’s local police station, but they said he wasn’t there. I suggested Hertford police station, as it was in Hertford where the adopted parents lived. Pierce did that and spoke with the inspector. I always remembered his reply: “We can neither confirm nor deny that an Albert Meltzer is here”. Bingo! (We never gave the inspector Albert’s forename.)

I rang Stuart with the details and he said he’d organise a QC and, if needed, someone to stand bail. He also provided a list of contacts. We agreed that Albert couldn’t spend one night more in cells as his health was not up to it. We had to move fast.

Throughout the night, several of us gathered in Brixton to utilise ‘free’ phones in squats to ring contacts that Stuart had provided. The next morning we drove to Hertford magistrates court. There the barrister was waiting (it was clear the magistrate was not expecting a QC) and also the person Stuart found who would stand bail – the historian Anthony Beevor. Surely nothing could go wrong now! Not so: the magistrate demanded £20,000 bail – more or less immediately. Beevor explained it would take a while to get that money together. It was looking like the magistrate would reject the offer, so I whispered to the QC that I would stand bail (that was a complete bluff – but we were desperate). Then luck turned in our favour: the magistrate agreed to go with Beevor after all and Albert was allowed to go.

Outside, as we walked Albert to the van we’d come in, he paused and asked what had happened during the night: the desk sergeant had said his phone never stopped ringing! And there were calls from some of Stuart’s contacts: Noam Chomsky, Nobel Peace Prize recipient Sean McBride, lawyer Lord Gifford, and even the head of the CNT anarcho-syndicalist union in Spain threatening a general strike! Albert didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

Some months later, the truth of what happened came out in court and the natural mother of the boy and Albert were acquitted of all charges.

End of an era?

When Albert died in 1996 it was like the end of an era. And with the death of Brenda and now Stuart, that feeling is consolidated. They and many others like them were of a different time, and they responded to the fascistic repression, particularly in Spain.

Today that repression is still found but taking different forms and in different places. It too needs resisting.

Stuart Christie is survived by his daughter Branwen and grand-children Merri and Mo.

Featured image supplied