A new report shows that the UK is putting itself at risk of another disease outbreak due to its vast trade in wild animals. Using data sourced through a Freedom of Information (FoI) request, the charity World Animal Protection has revealed that the UK legally imported millions of wild animals between 2014 and 2018.

The scientific community widely believes coronavirus (Covid-19) originated in wildlife and transferred to humans. This new report shows that the UK imports wild animals from almost half of the world’s countries, including those the charity described as “emerging disease hotspots”. In short, the trade is putting Britons at serious risk of further disease outbreaks.

Legal trade

As World Animal Protection noted in a press release, there’s been much discussion of the illegal trade in wildlife since coronavirus struck. But there is a huge legal market in wildlife that hasn’t attracted as much attention. It’s this legal trade that the charity focused on in its report.

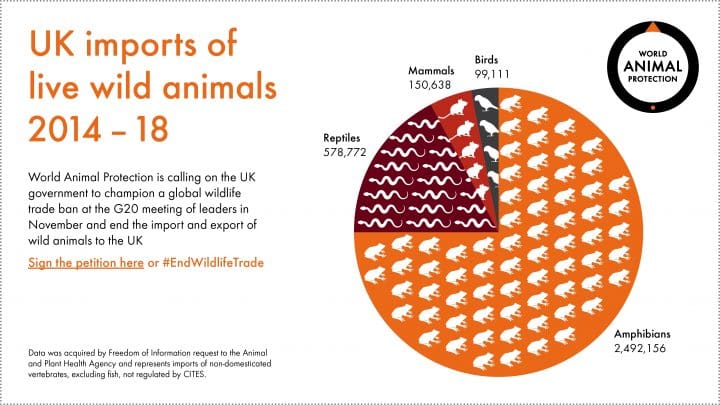

According to the data provided by the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA), the UK legally imported 3,411,021 wild animals between 2014 and 2018. Specifically, the charity requested figures for “non-CITES listed live wild vertebrates (excluding fish) for commercial purposes”. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) ‘lists’ and regulates trade in 5,950 different animal species. The future of these species are at risk, which is why CITES lists them. So the total figure of UK imports is even larger when considering the report’s exclusions – which included semi-domesticated pigeons and game birds. World Animal Protection found that over 48 million individual animals entered the UK during the time period it analysed. CITES-listed animals were not included in this total.

Of the nearly 3.5 million imported wild animals included in the report, 2,492,156 were amphibians and 578,772 were reptiles. Figures for mammals stood at 150,638 and 99,111 for birds.

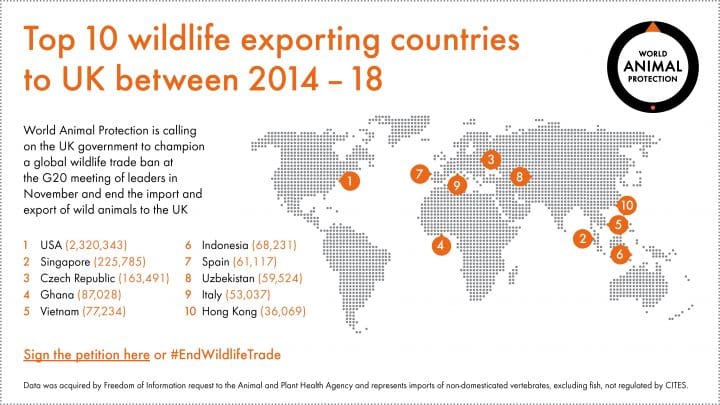

World Animal Protection found that these wild animals came from 90 countries spanning nine global regions. These included tropical regions in Asia, Latin America, and Africa, which the charity said are “identified as emerging disease hotspots”.

Worth the risk?

World Animal Protection says the imported reptiles, amphibians, mammals, and birds all pose risks in terms of public health. In particular, it warned:

Most emerging human diseases are thought to originate from mammals and their import represents a prominent public health concern.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) says previous human epidemics, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS), likely originated in other animals. Such diseases are called zoonotic diseases because they transfer to humans from other animals. World Animal Protection explained:

70% of all zoonotic emerging infectious diseases are thought to originate from wild animals and over 35 infectious diseases have emerged in humans since 1982, including COVID-19, SARS, Ebola and MERS. Importing animals in such numbers risks the spread of such diseases, caused by harmful viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites introduced into new environments.

As noted, World Animal Protection limited its report to wild animals that the UK imported for commercial purposes, including the exotic pet trade. Other purposes of the global wildlife trade identified in its report include fashion, traditional medicine, trophies, luxury goods, and food.

End the trade

To reduce the risk of future disease outbreaks, World Animal Protection is calling for a wildlife trade ban. But it’s motivation for that call doesn’t solely relate to humans. Wild animals obviously suffer tremendously to satisfy human trade in their lives. People abduct them from their homes, force them into captivity, and ship them off to whatever place – and for whatever purpose – their captor chooses. The situation is highly stressful for them, as Born Free explained:

Wild animals are collected, farmed, transported, exported and traded in huge numbers, more often than not enduring appalling conditions. Crowding, stress and injury among such animals provide the perfect environment for pathogens to spread and mutate, and their close proximity to people when they are traded and sold creates the opportunity for human transmission.

Furthermore, the wildlife trade contributes to the climate crisis. Because wild animals are a part of the vital ecosystems on which the planet’s health depends. That’s why World Animal Protection’s wildlife campaign manager Peter Kemple Hardy argues:

In a post-COVID world, we should demand nothing less than a global and permanent ban on the commercial wildlife trade, to protect wild animals, human health and the planet.

In short, for everyone’s sake, we need to end the wildlife trade, and there’s no better time than now to do it.

Featured image via Carl D. Howe / Wikimedia