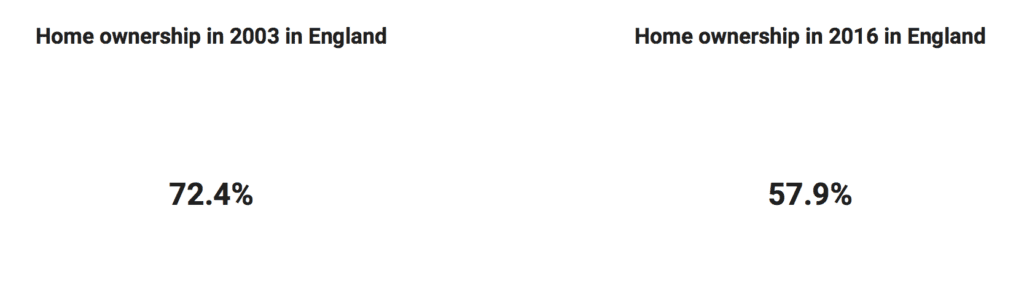

A report by the Resolution Foundation has revealed that home ownership levels in England are at a 30-year low. Years of rising house prices and low wage growth have left home ownership completely unaffordable for an increasing number of people, but the standard policy response is missing the point. It’s not more houses we need. It’s regulation, so that lower-income families can not only afford to buy, but to live.

The housing crisis in numbers

Research by the foundation shows that it’s not just London that’s been affected by a 30-year low in home ownership, but also northern cities such as Sheffield, Leeds and Manchester. In fact, home ownership levels have lowered across all parts of the country.

These new figures are a direct product of increased house prices, which are growing at a rate of up to 14%, and comparatively weak wage growth, which is currently at just 2%. This has been backed up by surveys such as the English Housing Survey, where two-thirds of private and social renters cited affordability as a barrier to home ownership.

Today, the average house price in England is between £211,230 and £227,000, while in London it is £472,163. Compare this with the average median wage, which is between £20,280 and £27,144 per year, and up to £36,088 in parts of London (taking out the City of London, Kensington and Chelsea, and Tower Hamlets). That means house prices are between eight and 13 times the median national wage.

While Scotland and Wales are experiencing housing shortages as well, the gap between earnings and house prices is not quite as stark. Median wages in Scotland linger between £24,388 and £27,144 while the average property value is £141,142 and increasing less sharply than in England. Median wages in Wales are a little lower, between £20,280 and £24,388, while the average property value is around £168,000.

Living standards and rent

The unaffordable reality for the average person owning a home is thereby painted in numbers. But home ownership and rising house prices aren’t the only consequences of the housing crisis. They have implications for the general economic well-being of ordinary people in England.

Stephen Clarke, a Policy Analyst at The Resolution Foundation, has said:

The shift to renting privately can reduce current living standards and future wealth, with implications for individuals and the state.

Then, there’s the fact that lower levels of home ownership have created a higher demand for rental properties and pushed rents up. This doesn’t just affect people’s ability to save to buy a home, it can also make the difference between getting by and not getting by, as Anne Baxter, Head of Policy and Public Affairs at Shelter, has explained:

Sky-high rents are leaving many families struggling to make ends meet each month, let alone save up enough for the deposit on a home.

Quite frankly, the ability to buy is the least of some people’s worries, given that the number of homeless households has risen to 50,000 a year.

The elephant in the room is that home ownership is not even an option for many people. And that’s why standard policy responses from both previous Labour manifestos and current Conservative mandates to increase the number of new homes being built miss the point entirely. The housing crisis is not just about people owning homes. It’s about people being able to live.

The emphasis on building new homes and making home ownership more accessible ignores the quality of life standards for low-income families. David Cameron’s pledge to scrap the rules around affordable housing is a prime example. Cameron’s argument that developers should be allowed to disregard rules about creating housing with capped rents in order to build more houses, however affordable they may have become, only serves those earning enough to save the amount needed for a deposit. Meanwhile, rents for those who cannot afford to buy go up and people are priced out of their neighbourhoods, maybe even pushed out onto the streets or into B&B accommodation.

Regulation

The other reason building more houses will not, on its own, solve the housing crisis is the fact that the market is allowed to continue unchecked with return on investment still the ultimate end-goal. Consider the impact of foreign investment, for example. According to a report by a Conservative think tank in November 2015, foreign buyers account for 10% of the UK stock, not only in London but in other regional hubs like Manchester as well.

Buy-to-let lending arrangements have also been favourable for buyers. Banks tend to prefer landlords because of their ability to front up cash. This ultimately means that those not using property as a specific investment vehicle pay, while those already on the property ladder can continue to reap the benefits of skyrocketing house prices.

Current Labour plans endorse increased regulation on rents and addressing affordability. The Green Party also rejects viewing housing as a means of ‘speculative investment’ and advocates viewing it as a basic and fundamental requirement for well-being, which means looking beyond local housing policies and integrating the issue with other social and economic factors.

Theresa May has acknowledged that the housing deficit will make the wealth gap more pronounced, and that expensive housing is not the answer to economic growth. But if she wants to tackle the true crisis, which is not just about ownership, she needs to steer her policies in the same direction as her parliamentary counterparts and view housing as an economic necessity rather than an economic advantage.

Get Involved!

Support the charity Shelter.

Read more articles on the housing crisis by The Canary.

Featured image via Flikr/GordonJoly

![Climate change unleashes “Siberian plague” on nomadic reindeer herders [VIDEO]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/RIAN_archive_501303_Aircraft_delivered_cargo_for_reindeer_herders1.jpg)

![The BBC just let slip the real reason for its biased coverage [EXCLUSIVE]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/bbc-building-min.jpg)