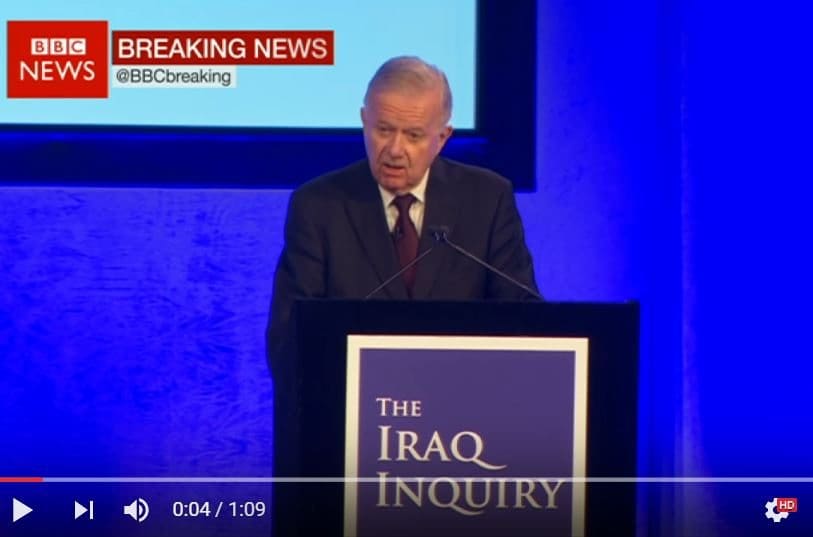

The long awaited report from the UK government’s inquiry into the decision to go to war in Iraq is going to be released on Wednesday.

But make no mistake: the process was designed from the start to let decision-makers off the hook for their roles in an illegal invasion that has destroyed a country and paved the way for the rise of the Islamic State.

A hint at the report’s findings were revealed by Lord Butler, who led a previous 2004 Iraq inquiry, which concluded that while Tony Blair had been “wrong” about Saddam Hussein’s WMD capacity, he did not deliberately deceive anyone:

“You can see the mistakes that deceived the intelligence community into thinking Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. I have talked to the agencies and I hope that they have learnt the lessons from that,” said Butler.

Conflict of interest

Sir John Chilcot, who chairs the current inquiry, was a member of Butler’s team for that previous inquiry. The secretary of the current inquiry is Margaret Aldred, who was previously deputy head of Defence and Overseas Secretariat (subsequently Foreign and Defence Policy Secretariat).

According to the Cabinet Office Annual Report and Resource Accounts for 2004/5, when Aldred began her role:

The Defence and Overseas Secretariat (DOS) has been at the forefront in coordinating the Government’s policy in Iraq following the end of the conflict with regular meetings of ministers, senior officials and video conferencing with officials in Iraq. Over the past year, DOS has coordinated policy development on Iraq.

Yet Aldred herself, despite being someone involved in the government’s Iraq policy, has not been called as a witness to the inquiry – although her successor in the same post was.

Chilcot and his aides refused to disclose information on Aldred’s own role in government policy on Iraq. As noted by Chris Ames, editor of the Iraq Inquiry Digest which has tracked the inquiry since it began:

The Inquiry’s willingness and ability to reveal the extent of her role is clearly compromised by the fact that she is its secretary. In concealing the conflict of interest, the Inquiry is concealing the truth of what happened.

Ames noted that the inquiry would have “little credibility” if it refused to come clean about its own connections to the government’s Iraq policy.

The first casualty

This should not be a surprise given that the first inquiry by Lord Butler was already a bankrupt whitewash of the highest order.

Butler’s report (6.4 para, p. 499), for instance, claimed it was “well-founded” that Saddam Hussein was trying to illegally obtain uranium for his so-called advanced nuclear weapons programme, from Niger and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The allegation was based on forged documents, which Butler claimed the British had no idea were forged.

Butler’s pathetic, fantastical version of events is so astonishingly absurd that it is not taken seriously by any journalist or historian who actually understands the Niger uranium intelligence scandal. Yet somehow in legitimate public discourse, it is still considered credible – and Butler receives ample air time with a straight face, without a single question about his role in obscuring the facts.

Don’t worry, you’re not going mad. This is the exceptional state of British journalism today.

In 2012, I and a team at the Institute for Policy Research & Development conducted our own peer-reviewed independent investigation into the public record data concerning Saddam’s alleged efforts to get uranium from Niger.

In our report, Executive Decisions: How British Intelligence was Hijacked for the Iraq War – which was submitted to Chilcot’s inquiry – we pointed out that Britain’s White Paper on Iraqi WMD made the uranium claims, despite the British having being warned by George Tenet, head of the CIA, not to include them.

The claim traces back to ‘intelligence’ that was examined and discredited way back in 1999. Falsified documents were discovered in the form of written correspondence between officials in Niger and Iraqi agents. The documents had been submitted to the CIA by British officials.

But the documents were quickly dismissed at the time and found to be crude forgeries containing laughable errors: names and titles not matching individuals in office at the time; the Niger government’s letterhead being obviously cut and pasted, and the signature of a government official who had retired long ago having been forged.

Senior officials from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) described the documents as “so bad” that he could “not imagine they came from a serious intelligence agency.” The IAEA confirmed the forgery within hours.

But years later, this rank bullshit still made it into Britain’s official ‘intelligence’ assessment of the state of Iraq’s WMDs. It was then conveniently quoted by President Bush in his State of the Union address to Congress in 2003, helping to rile up public support for war.

Sadly, you won’t find the self-righteous pundit class lambasting the venal culture of self-serving power that allowed the systematic concoction of such “conspiracy theories” against official enemies to flourish in the heart of Whitehall.

Lies? What lies?

And here lays bare the methodology of vindication to be deployed by Chilcot and his friends: admit real failures, loudly condemn officials for failing, but contextualise the decisions leading up to the failures as entirely unintentional, then ultimately blame the failure on faulty systems across government.

The most that Blair and his warmongering friends can be accused of, then, is bad management.

But here’s the reality: the regurgitation of discredited forged nonsense as ‘British intelligence’ – which had already been rejected by the CIA and IAEA – speaks not to ‘faulty intelligence’ but to the deliberate ‘politicisation of intelligence.’

But false intelligence did not make its way inexplicably into the intelligence system because our intelligence agencies are underfunded and badly organised, and really, really believed what they were saying, poor darlings.

It made its way in, because political leaders made pre-conceived, ideological decisions about going to war.

Those decisions were untenable if the intelligence wasn’t there to back their decisions. So they exerted massive pressure on the intelligence community to find or make that intelligence.

Cherry picking

In leaked UK government memoranda between March and July 2002, references are repeatedly made to “poor” intelligence about WMD, and the “thin” case for war that it presented.

Indeed, then head of MI6, Richard Dearlove, confirms that “the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy” of regime change, “justified by the conjunction of terrorism and WMD.”

Senior intelligence officers in MI6 and the CIA also confirmed that intelligence was being deliberately manufactured to support “the opposite conclusion from the one they have drawn.”

One MI6 officer said:

You cannot just cherry-pick evidence that suits your case and ignore the rest. It is a cardinal rule of intelligence. Yet that is what the PM is doing.

And a CIA official concurred:

We’ve gone from a zero position, where presidents refused to cite detailed intel as a source, to the point now where partisan material is being officially attributed to these agencies.

Chilcot’s abject failure to get to the bottom of this reveals the extent to which our democratic checks and balances in foreign policy decision-making are fundamentally broken – and confirms the institutional lack of accountability that allows this broken system to continue unabated.

The Chilcot report will be used to let the people who lied their way into war off the hook. It will also reinforce the idea that they did so with unquestioned benevolence, despite terrible and regrettable failures of management and judgement.

Don’t be surprised to find much of the pundit class – who, by the way, overwhelmingly and shamelessly clamoured for the invasion – chorusing in agreement.

They have blood on their hands too.

Image via Flickr/Jason

![The Sun’s Chilcot coverage shows how utterly hypocritical they are [IMAGES]](https://www.thecanary.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/sun-iraq4-2.png)