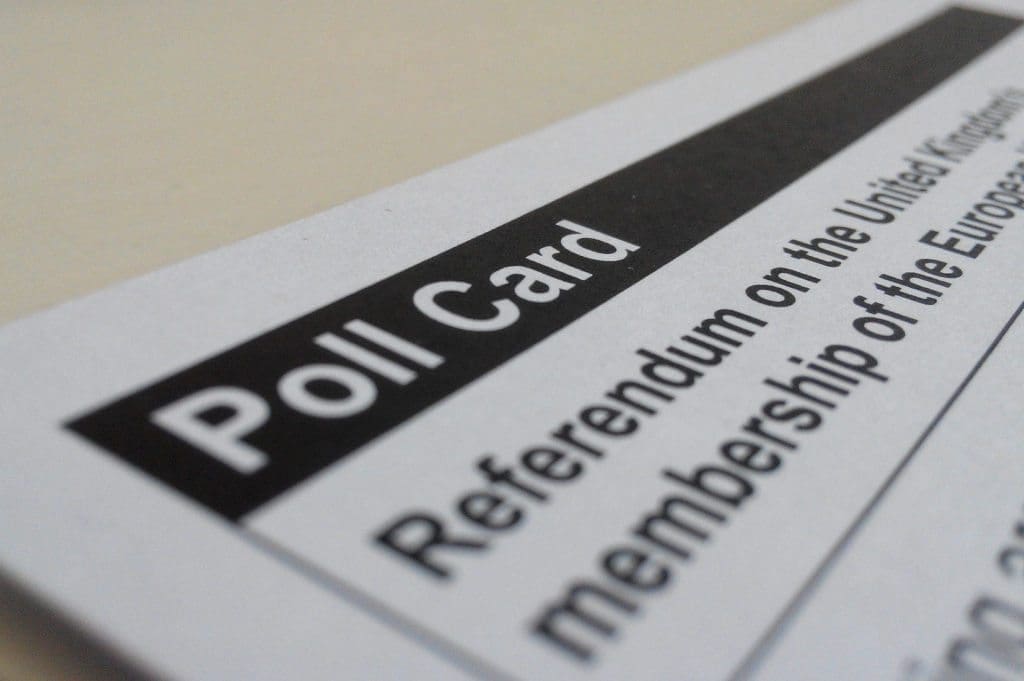

Following the Brexit storm what remains is wide “uncharted territory” that at some point will have to be trailed. Once the government invokes article 50 of the EU Lisbon treaty, the EU and the UK will have two years to come up with new agreements.

But before article 50 is triggered, the scientific community, which largely supported the Remain side, has already got down to work to minimise the possible losses, and is trying to make the best of the situation.

The grassroots campaign Scientists for EU, who barnstormed to keep the UK within the EU, is gathering stories on the impact of Brexit on UK science. According to Mike Galsworthy, one of the founders of the campaign, the idea is “to catch fallout problems early and implement remedial measures”.

Science funding, researchers’ mobility and management of ongoing European projects are among the issues that will have to be tackled in future agreements.

Applying for EU money. The UK is one of the main recipients of EU funding for research. According to a 2015 Royal Society report, between 2007 and 2013 the UK received circa €8.8bn from the Horizon 2020 program and the EU Structural Funds.

Even after Brexit is accomplished, the UK could still apply to EU funding schemes by becoming an “associate” member and paying an annual contribution proportional to their GDP. There are currently 15 non-EU countries participating in this way, the main problem being the lack of influence in the decision-making over the funding.

Reaching fruitful agreements that allow the UK to apply to EU funding would be a win-win situation, as the UK would see its funding for research increased, while the EU would benefit from the UK’s expertise and top facilities.

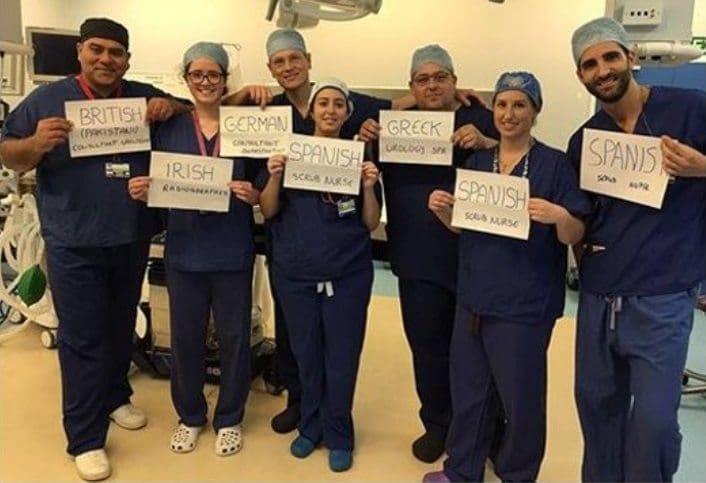

Movement of scientists. The UK scientific system relies heavily on a foreign, highly qualified workforce, with some estimates that as many as one in every four members of the academic community in the UK comes from abroad. EU nationals working in the UK are now pondering whether and under what terms they will be able to stay. This uncertainty also affects PhD students and postdoctoral researchers, many of whom rely on fellowships rather than work contracts.

While it is unlikely that their situation will change overnight, it is crucial that the future migration agreements protect those EU nationals already working in the UK. The agreements should also seek to attract foreign talent, as the lack of free movement could have an impact on the recruitment of students and researchers from other European countries.

A cautionary tale, regarding both migration and funding, is that of Switzerland, which had its EU funding cut off following a referendum where tougher migration regulations were imposed.

Existing EU infrastructure. One of the big questions after Brexit is what will happen to EU research facilities and agencies hosted by the UK.

One of these organisations is the European Medicines Agency (EMA), which is responsible for the “evaluation, supervision and safety monitoring of medicines developed by pharmaceutical companies for use in the EU” and is currently headquartered in London. Experts believe that the agency, along with its 600 full-time employees, will likely have to relocate to another country.

The relocation will also affect the UK’s national Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), that currently works in tight association with the EMA. The MHRA will have to decide if they want to partner the EMA (which also benefits from the UK’s expertise) or develop an independent national drug approval system.

UK-based pharmaceutical companies, such as GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson have urged “the UK government to promote political stability” and have promised to engage in the process of moving forward.

Another key facility is the Joint European Torus (JET), Europe’s largest fusion reactor. Owned by Euroatom, the nuclear division of the EU, JET is located at the Culham Science Centre, near Oxford, and is collectively used by more than 40 European laboratories. Steve Cowley, director of the Culham Science Centre, admitted days before the referendum that a Brexit “certainly will make us very vulnerable”. The short-term future of the project is secured, as the current contract to operate the reactor expires in 2018, but in the long-term new collaboration terms have to be set with the UK. According to Tony Donné, EUROfusion Programme Manager:

Our British member , CCFE, is a strong contributor to the European fusion programme. We will be working hard to continue the collaboration after 2018. If and how this is possible is impossible to say today,

JET’s role is crucial for European interests, as it is the testbed for a larger fusion project called ITER, whose current members are China, the EU, India, Japan, Korea, Russia and the US. ITER is currently under construction in southern France and aims to prove the feasibility of fusion as a large-scale source of clean energy. Should the project succeed, it will pave the way for future fusion power plants.

ITER has released a press note stating that the future of the project is not jeopardised by Brexit, as the political changes are likely to take years to happen, and the European membership in ITER is through Euroatom, which is legally distinct from the EU. However, the conditions of the UK membership to Euroatom will have to be reviewed and renegotiated in the near future.

Other European facilities such as CERN, the European Space Agency or the European Molecular Biology Laboratory will not be so affected by Brexit, as they are not under EU control.

Get involved

Help to monitor the effects of Brexit on UK Science

Featured image via Flickr/Anna & Michal