This week, roughly 700 migrants drowned in the Mediterranean. With statistics about the ‘migrant crisis’ now a daily fixture of the news cycle, perhaps this latest one doesn’t shock you. Compare it to the statistics for the entirety of 2014 and 2015 however, and the reality of that number hits home rather harder. In each of the last two years, around three and a half thousand men, women and children died, escaping difficult lives.

In this one week of 2016 alone, almost a quarter of that amount of people drowned.

Overwhelmingly, the reaction to the intensifying migrant crisis (read: hundreds of vulnerable people drowning at once) is: “how will this trend affect me? And the British economy? And the EU referendum result?”

This response is grounded, truly, in the difficult lives of people in the UK. Facing crises of our own – personal, nationwide, and international – we fear not only for our future but too often for our present. We are living in poverty, we are struggling to find security, we are under threat from those who want to harm us. And we must hold on to our genuine concerns and our very real crises at the same time as understanding how they relate – or not – to the migrant crisis.

It has become too often spun as a crisis faced by us, rather than a crisis faced by migrants. And this is only fueling the misunderstanding of where our own problems really stem from, as well as of the crisis of people dying en masse. When we play our problems off against each other, we lose an opportunity to take control of them.

Britain’s many crises

We have a financial crisis, housing crisis, job market crisis, governance crisis, health service crisis…none of these issues, currently swirling around the typhoon of sleaze that is the EU referendum debate, emerged from the migrant crisis. The issue of people coming to the UK and putting pressure on these crises is, of course, at the forefront of many people’s minds, but ultimately the causes of and solutions to these issues stem from the management of resources and opportunity.

That management is dependent on decisions made by those in power, i.e. those in government, and/or those who have a lot of money. They do not stem from fluctuations of the population by less than 1% – net migration to the UK was 323,000 in 2015, almost exactly 0.5% of the population of Britain, estimated to be 65m.

Oxfam’s case study of austerity and inequality in the UK found that the “socio-economic reforms” enacted by the Thatcher government and continued under New Labour, the coalition and the Conservatives:

…led to a dramatic increase in the number of people living in poverty, which almost doubled, from 7.3 million people in 1979 to 13.5 million in 2008.

This was made worse, of course, by the financial crisis of 2008. The government’s response of ramping up policies that benefited those with money and sacrificed those without have resulted in a crisis-ridden society for millions:

Economic stagnation, the rising cost of living, cuts to social security and public services, falling incomes, and rising unemployment have combined to create a deeply damaging situation in which millions are struggling to make ends meet. […] As millions more are expected to be living in poverty and at risk of poverty by the end of the decade, the richest look set to get richer.

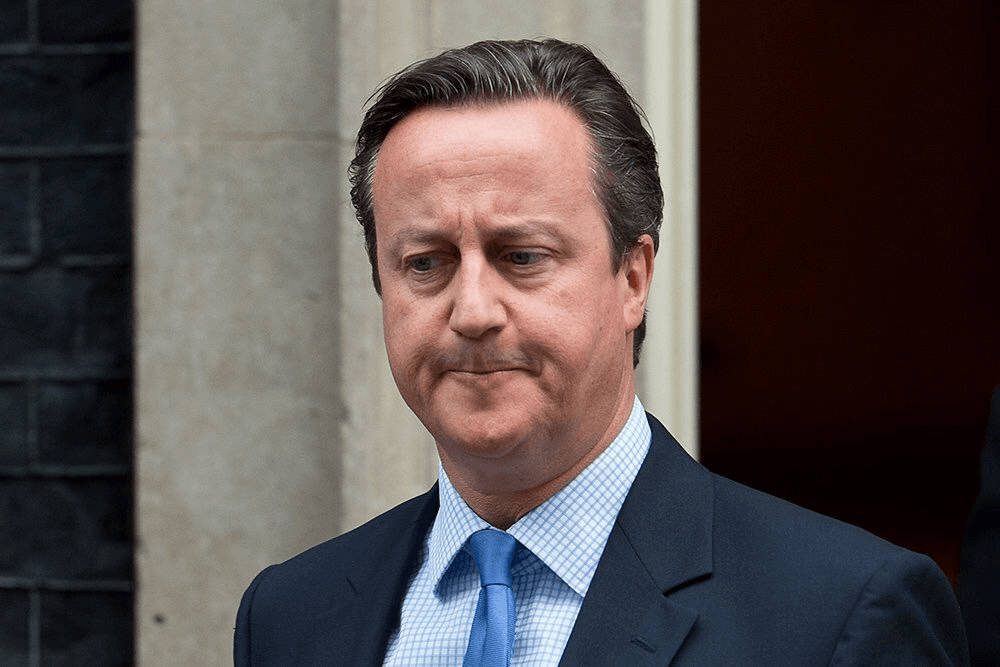

The topic of migration can be abused as any other, and recently the EU referendum is at the forefront of opportunist exploitation of the issue. Only two years ago, David Cameron said:

I believe that immigration has brought significant benefits to Britain, from those who’ve come to our shores seeking a safe haven from persecution to those who’ve come to make a better life for themselves and their families, and in the process they have enriched our society by working hard, taking risks and creating jobs and wealth for the whole country.

Political pressure now upon him from ‘Brexiteers’ scaremongering around the issue of rising immigration, the Prime Minister takes a quite different tone these days. And those in the Brexit campaign are using the issue almost daily as political ammunition.

The migrant crisis is not the primary, significant threat to Britons’ wellbeing that many citizens, MPs and pundits are claiming it is – whether they truly believe it or not. The way that power and economics interacts is the most significant factor in determining our quality of life.

Abusing one crisis, ignoring another

The political ‘establishment’ – that is, those in the revolving doors of power in the political media, government, and the private sector – has a lot to answer for in our understanding of this. They largely set the tone of the public debate, using language and parameters that close down wider understanding and co-operation. A prime example of this is the highly selective and misrepresented EU referendum debate, not least Priti Patel MP’s recent article for the Telegraph in which she criticised the leaders of the ‘Remain’ movement for being ‘too wealthy’ to understand people’s concerns about immigration.

Patel claims:

If you have private wealth or if you work for Goldman Sachs you’ll be fine. But when public services are under pressure, it is those people who do not have the luxury of being able to afford the alternatives who are most vulnerable. […] It’s shameful that those leading the pro-EU campaign fail to care for those who do not have their advantages. Their narrow self interest fails to pay due regard to the interests of the wider public.

Patel’s narrow self-interest, then, fails to pay due regard to her own political party’s far larger contribution to the inequality and vulnerability of Britons, by those who have private wealth and/or work at Goldman Sachs. Her attempt to appeal to vulnerable voters by positioning herself as ‘standing up for the little guy’ is hugely disingenuous. In the same week that hundreds of people – some with skills, some perhaps not – drowned, she stated:

A meritocratic immigration system would not only be fairer, it would also be better for Britain because we would be getting the brightest and most productive people contributing to our economy rather than unlimited numbers of often unskilled migrants from Europe.

She then finishes with the unsubstantiated claim:

Freedom from the EU can only be beneficial for our country.

This is yet another needlessly manipulative interjection into the EU debate which, on both sides, has descended into embarrassing hysteria. Nobody knows what the outcome of the EU referendum will be, regardless of the result. The details will be worked out after the referendum, and either a Leave or Remain vote is a vote for Neoliberal economics and austerity that will damage ordinary people.

Solidarity

Ultimately, the majority of Britons have far more in common with migrants needing financial, physical, and emotional support than we do with those of the political and corporate class. As the leaders of teams Remain and Leave indoctrinate their followers to focus the issue of ‘illegal aliens’ at the forefront of the debate, they hold on to their inequitable share of power, and various assets, while refusing to discuss the impact that they and those at the top of the pecking order have on the well-being of British people. As author Irvine Welsh says:

The roll-call of suits droning on about “business”, “trade” and “regulation” drives home that the argument is essentially a neoliberal one: does the EU or an independent UK offer us the best opportunity to rip off our citizens?

The definition of the ‘migrant crisis’ is fast becoming the inability to understand it, and therefore an inability to make substantial, long-term efforts towards helping to end it. The crisis of inequality, which contributes to the migrant crisis, is far more important in our current situation. And the waves of people dying, rather than waves of migrants arriving, is the true problem on our doorstep that those leading the public debate want us to ignore.

Get involved.

Find a way to donate to refugee causes.

Write to your MP about the migrant crisis.

Image via Irish Defence Forces