The government has announced the “biggest shake-up of prisons since Victorian times”. But while the media focuses on ‘iPads for prisoners‘ and ‘weekend inmates‘, the real story is in the handing of new financial powers to prison governors, allowing them “unprecedented levels of control over all aspects of prison management”. The government is using the academies model to privatise our prisons through the back door – and the results will be just as disastrous for prisons as they have been for schools.

In the Queen’s speech on Wednesday, the government announced its new prison and courts reform bill. At the heart of the bill is the creation of several new “autonomous reform prisons” which, says the government:

will give unprecedented freedoms to prison governors, including financial and legal freedoms, such as how the prison budget is spent and whether to opt-out of national contracts; and operational freedoms over education, the prison regime, family visits, and partnerships to provide prison work and rehabilitation services.

The academisation of prisons

If all of this sounds familiar, that’s because it is. The reforms are based on the academies model, as David Cameron admitted in a speech he made about the reforms in February of this year:

It’s exactly what we did in education — with academies, free schools and new freedoms for heads and teachers.

They were even introduced by the same man, Michael Gove. As Education Secretary in 2010, Gove said: “We trust teachers and headteachers to run their schools.” Now, as Justice Secretary, he says: “By trusting governors to get on with the job, we can make sure prisons are places of education, work and purposeful activity.”

As with academies, the introduction of reform prisons will be rolled out gradually. Six prisons will be turned into reform prisons by the end of this year. More prisons will follow later this parliament, and the government’s nine new super-prisons will also “be established with similar freedoms”.

And, as with academies, the prison reforms will open up commercial opportunities for those in charge of them. Prison governors will have “unprecedented operational and financial autonomy”, says David Cameron. They will be given “total discretion over how to spend” their budgets. They will be able to “opt-out of national contracts and choose their own suppliers”. And, just to be clear, “we’ll ensure there is a strong role for businesses and charities in the operation of these Reform Prisons”.

We know what happened when academies were handed power over their own budgets and contracts. They used that power to pay themselves millions in taxpayers’ money – both on their own salaries, and on contracting out services to companies they or their families own. And now the government seems to have gone to some effort to replicate that experience in reform prisons, by establishing them “as independent legal entities with the power to enter into contracts; generate and retain income; and establish their own boards with external expertise”.

Overcrowded and underfunded

The stated aims of the government’s reforms are laudable, and desperately needed. The government says (pdf) it wants to reduce reoffending rates, and to ensure our prisons are “places of rehabilitation”.

But experts say the government’s reforms won’t solve the real problems that stand in the way of rehabilitation: overcrowding and underfunding.

Prison staffing levels have been cut by 30% since 2011. Overcrowding is at unprecedented levels, with more than 12,000 prisoners being held two to a cell designed for one. Prisons are now so overcrowded and underfunded that violence and self-harm are rife, and riot squads are called out daily.

As a result of poor staffing levels, many prison education and training classes are half empty for want of staff to escort prisoners to class. Introducing new classes – no matter which “further education colleges, academy chains, free schools or other specialists” governors now have the powers to bring in – is unlikely to help with rehabilitation, unless funding for prisons is also increased.

And far from resolving the overcrowding problem, the government’s prison plans will likely exacerbate them. Michael Gove has ruled out reducing the prison population. Instead, the government’s nine new super-prisons, to be paid for by selling off inner city sites to developers, will prioritise efficiency over rehabilitation, cutting spaces like communal dining rooms in order to cram more prisoners in and reduce the numbers of staff needed to supervise them.

The road to privatisation

The logical end point of the government’s prison reforms is the private management of our prisons – a process that began in the 1990s and continues apace. Private contractors like G4S and Serco now run 14 prisons in the UK, and their prisons have been plagued with controversies, and criticised for being poorly run. To understand their priorities, we need to look no further than their treatment of detainees in immigration centres, where private contractors been accused of using detainees as cheap labour and asylum seekers say they are ‘treated like animals’ .

Meanwhile, the much-touted rationale for privatisation – benefits to taxpayers – has failed to materialise. According to the government’s own figures (pdf), private prisons cost more than state-run ones, despite having lower staff-to-prisoner ratios.

Our prisons are in crisis and are in desperate need of reform. But, as the lesson of academies should have taught us, reforming public services by opening the door to private interests will only serve profit, not people.

Get involved!

- Sign the petition to keep our prisons public.

- Support The Prison Reform Trust.

- Support The Howard League for Penal Reform.

- Support The Canary, so we can keep holding the government to account.

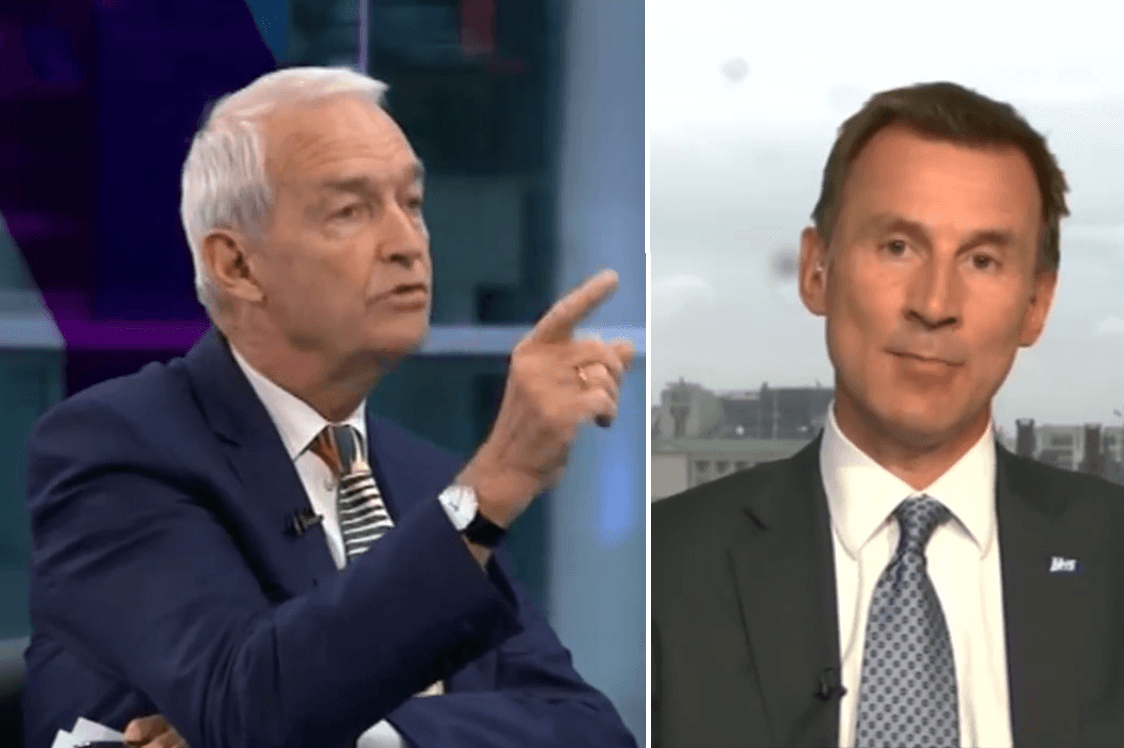

Featured image via Guardian screengrab.