The BBC has uncovered video of a secret lecture given by double agent Kim Philby, an MI6 operative who delivered state secrets to the Soviets during the Cold War, and he has a lot to say about the British class system.

The footage of “Britain’s Biggest Traitor” addressing the Stasi – the East German intelligence service – is from 1981. Found in official archives of the Stasi in Berlin, the recording provides the first glimpse of Philby discussing his life and work. He begins, “Dear Comrades…”

What is particularly notable about the revelations – above and beyond the novelty and excitement of knowing truths previously hidden – is Philby’s unique insight into the workings of British institutions. Not simply their names, faces, or mechanics of their bureaucracy, but the dynamics of social class and how it facilitates (or not) ones ability to take advantage of situations.

Philby’s perfect ‘RP’ (or ‘BBC English‘) accent alone demonstrates that his class status may well have helped him along any career path he had chosen. But the man is candid – due to the fact that the tape was supposed to remain secret, says the BBC – in telling his German audience that he got away with his double life because his equally well-heeled colleagues would never accept that ‘one of their own’ would betray them. He was, he reminds them:

born into the ruling class of the British Empire.

What this meant for him as a young man entering the world of work was that he was implicitly trusted. An upper class, and thus – at the time, inevitably white – male, his journey from unemployed activist to MI6 operative took years, but came up against few obstacles. A graduate of Cambridge University, finding a job as a journalist at The Times led to:

building up contacts in the establishment and then as war came dropping hints about his desire to work for government.

Philby describes:

that he simply made friends with the archivist who managed the files by going out two or three times a week for a drink with him.

This allowed Philby to get hold of files which had nothing to do with his own job.

Because Philby was ‘one of them’ he could easily access documents he wasn’t supposed to, following his smooth path to the innermost chambers of government.

Twice, MI6 even cottoned on to Philby’s deceit – he was asked to resign after being suspected of spying for the Soviets, but was then taken back. When new evidence came to light of his deception, the MI6 officer watching him allowed him to escape by nipping off to do some skiing. Philby claims that as well as not wanting to believe him a traitor despite the evidence they had, MI6 would have a lot to lose were they to confirm it. This helped him avoid capture.

The revolving doors of power still work in a similar way. A sense of authority often comes not only from having money, and therefore power, but also a certain social status or appearance. Coming from a background of privilege does not make one a moral, loyal or even helpful person to have around, of course.

Journalist and author Owen Jones describes this setup in his book ‘The Establishment‘. He argues that rather than a secret conspiratorial effort, the establishment is more or less a bunch of people with power who want to hold on to that power. It follows that a lot of those people are born into the power they’re guarding – members of the ‘upper classes’.

In addition, the establishment is partly formed by those from the working and middle classes who have risen to prominence through business acumen and acceptance of the culture of the establishment (a culture Jones and others call neoliberal.) This corporate culture holds profit, and the power it brings, as its highest value. As long as one appears to have the ability to manage their role as a ‘good businessperson’ should – with all the assumptions and connotations both words entail – they are fit for the job.

An example of this is described by activist and co-founder of Greenpeace Paul Watson. He notes that Greenpeace was in essence taken over by people who accepted the corporate view of the environment as a resource. Watson, who left the organisation long ago, describes his frustration with the formerly grassroots project in an interview for the film END:CIV:

People who’re at the top of the totem pole now aren’t environmentalists; they’re fundraisers, they’re accountants, they’re lawyers, they’re businesspeople […] It’s not strange when people say to me, ‘the former President of Greenpeace now works for the logging industry of Canada; the former director of Greenpeace works for the mining industry; the former President of Greenpeace Norway works for the whaling industry.

See – because it’s just one corporate job to the next.

This is also true of politicians, and is why they’re often so generous to corporate power. They have an interest in pleasing potential future colleagues and employers.

There is much more to class and social mobility than simply personal finances, of course. Much of it is cultural, and that is well represented in the ease of interaction, social capital and recognition of status that Philby used to infiltrate the government. Much of the time, those who don’t conform to the rules of the elite, neoliberal, establishment class will be ousted from positions of authority, if they manage to gain them at all.

The British class system has eased slightly from the rigidity it held during the time Philby was recruited as a spy. But there’s no doubt that in real terms, it remains very much alive.

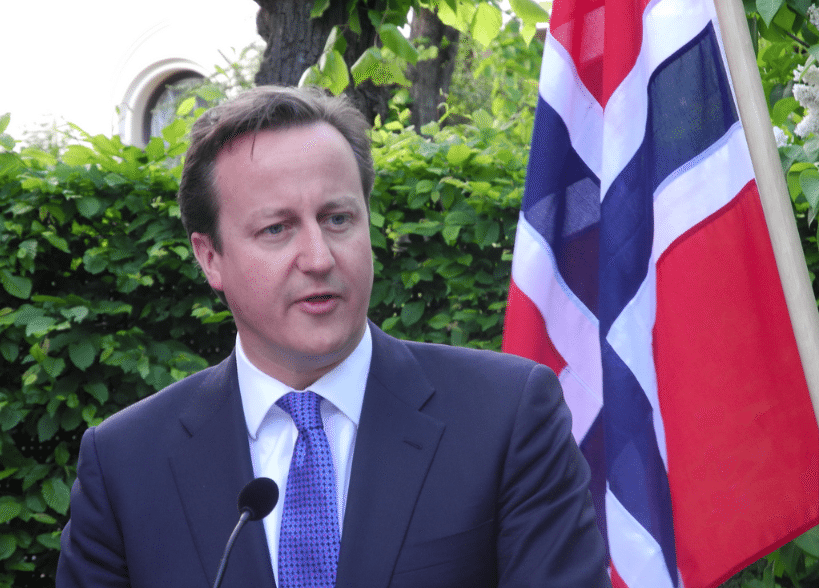

Image via viorel popescu/flickr