The Buckland Review into autism in the workplace, published in February last year, was a damning report led by Sir Robert Buckland, and aimed to address the many barriers that autistic people face in employment.

Autism in the workplace

Statistics from the report portrayed a bleak picture for those that are autistic, with employers expressing a hesitancy in terms of hiring, with 69% of bosses stating that the cost of reasonable adjustments was a primary reason and a staggering 29% of managers having fears over whether:

autistic people could do their jobs properly.

Currently, employers appear reluctant to hire disabled staff, as the Buckland Review concluded that 50% of managers expressed discomfort in terms of hiring disabled people.

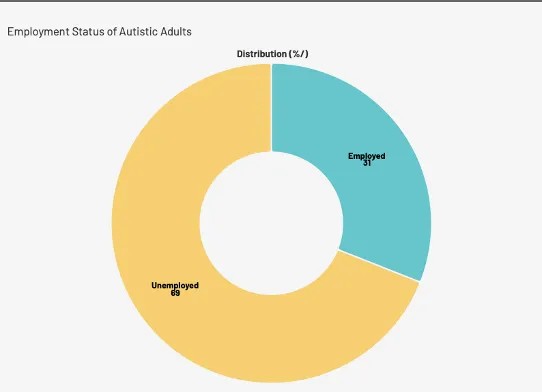

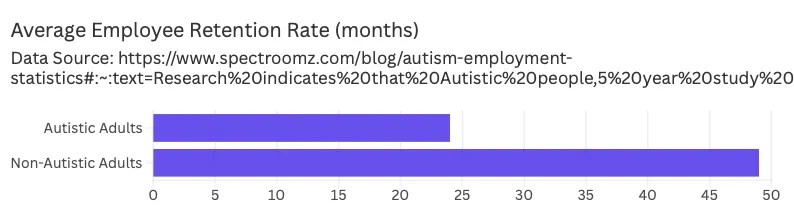

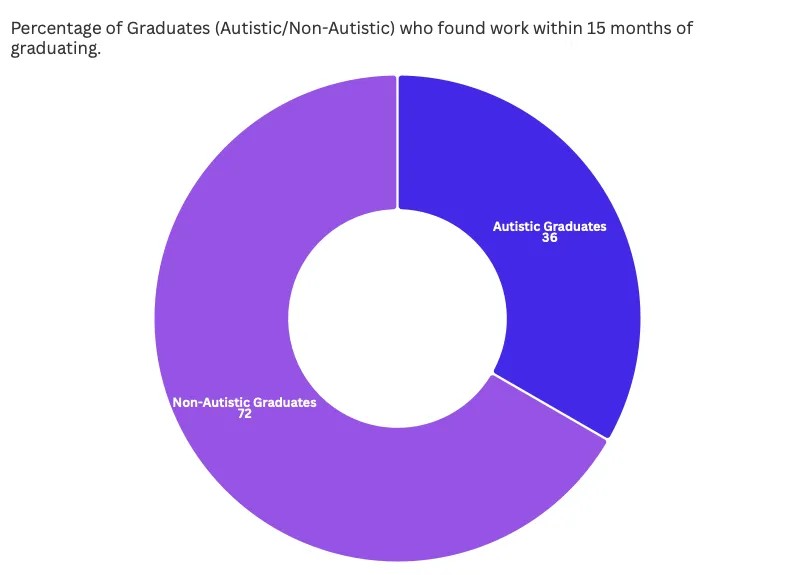

Below are more statistics from the Buckland review, which display the disproportionate treatment that autistic people face compared to their neurotypical peers. The difference couldn’t frankly be more stark, as autistic people face the:

largest pay-gap of all disability groups, receiving a third less than non- disabled people on average.

Behind these statistics, however, are real people who are struggling with finding financial independence, as well as experiencing deteriorating states of mental health and self-worth due to these severe employment barriers.

As part of the investigation, both Jayne Campbell and Pete Wharmby were interviewed and their stories are a captivating insight into how autistic people experience the workplace, with their accounts painting a gloomy picture.

Pete Wharmby – author of Untypical

Pete Wharmby, the author of Untypical, was diagnosed with autism at 34, and has immersed himself in raising awareness through speaking at events and publishing content on social media.

Speaking about Untypical, he told me that after discovering neurodivergent communities online he was encouraged to write his book, as he saw how much the “autistic community was really struggling”.

An English teacher at heart, writing the book came naturally to Pete and so, all his:

angry thoughts and all of my feelings of this isn’t fair, and I want things to be better, became Untypical.

When asked about his own experiences in the workplace, he said, the reason that he survived in teaching for so long was because he could “hide in his classroom”.

The NHS also points out that offering employees a quiet space to work is a reasonable adjustment that could help autistic people to feel less overwhelmed.

Pete, who also has ADHD struggles with organisational skills, which he believed was “very frustrating for my employers” even though he excelled at his job, always felt he was:

very bad at the political side of things, so the networking , and the office politics.

No ‘dream workplace’ for autistic people

Currently, he said the “dream workplace” for autistic people feels like a “pipe dream”.

He added to this by saying:

there would simply be more difference. You would notice it visually the moment you walked into a company building, or an office.

As everything feels so exemplified for autistic individuals, it can be hard, to feel at ease in a work environment, where they are in Pete’s opinion forced to experience a:

Victorian style of work, where everyone is expected to do the same.

This robotic and arguably capitalist way of working is something that Pete argues against, as this simply fails to accommodate for those who cannot perform in the same way that their neurotypical peers do.

He said that employers need to have serious conversations with their neurodivergent employees about what reasonable adjustments they would benefit from and not “assuming that a blanketed approach works for all autistic individuals”.

Recognising the neurodivergent community as people who can contribute to the economy and society, is also something that Wharmby promotes, and research supports this as statistics show that for certain jobs autistic people can be “45–145%” more productive than neurotypical staff due to their unique ability for hyper-focusing.

Jayne Campbell – from Citizen’s advice, formerly of Scottish Power

Jayne Campbell discussed her employment tribunal which found that Scottish Power had failed to put reasonable adjustments in place for her after she received a diagnosis of autism.

At first, Jayne excelled in the company. However, things soon took a turn for the worse, due to the increasing pressures of the job, and the toxic work environment which she simply couldn’t continue to ignore. This caused her mental health to deteriorate, and eventually Jayne was diagnosed as autistic.

After Jayne’s diagnosis, she had hoped that things would change, and like others, she felt that “they were really unsupportive” of her mental health, with as little as 4 in 10 participants of the “Diverse Minds Employment Survey” saying that disclosing to “their employer had a positive impact”.

The tribunal found that the company had categorically failed to make the necessary adjustments that Jane had asked for, including working from home and changes to her contracted hours, which made her feel that they “they were really unsupportive”, of her mental health.

On multiple occasions, the stress was so overwhelming for Jayne that she couldn’t go into work, and instead of being supported, she was told that:

you’re setting a bad example for the rest of the team.

When the pandemic arrived in 2020, she began to work from home, which came as an unlikely welcome relief to Jayne who said:

I think being able to work from home saw me through.

However, after the Covid pandemic, remote working was suddenly put to a stop as Scottish Power insisted that:

we need to keep an eye on you in the office.

After questioning this decision, and receiving backlash from her manager, she decided that “within that workplace, if you ask questions and talk back” it didn’t work, so she became “conditioned to just accept rules” even though Jayne was rightfully entitled to ask for reasonable adjustments.

Autism in the workplace: things must improve

Things however, didn’t stop there, as a new female manager arrived who began to order Jayne to “send everything that I’d done that day”, which led to her feeling like she was being:

treated so differently to anyone else on the team.

This simply led to Jayne having “more panic attacks” and even “hallucinations”. Since leaving Scottish Power, she hasn’t experienced these again.

At one point, things got so serious, that her manager “screamed down the phone” and said:

what are reasonable adjustments? Nobody could have those kinds of flexible hours!

After the ordeal, she “lost all enthusiasm” for work-related activities, as her experience with Scottish Power left her deflated and traumatised, leaving a lifelong scar upon Jayne who continues to battle with her mental health.

Since then, Jayne has managed to secure employment at Citizens Advice, Liverpool, and although the position comes with a reduction in salary, she has felt supported by her manager and was sent a “massive list of reasonable adjustments” including flexible hours and remote working.

She believes that the government and employers need to:

ensure that workplaces have specific rules relating to neurodiverse people, that are created by neurodiverse people themselves.