The NHS is still spectacularly failing to end its shameful institutionalisation of learning disabled and autistic people via the 1983 Mental Health Act (MHA). That is, nearly ten years on from its initial promises to vastly scale back the practice and shift to a model of supported living in the community, it’s still detaining learning disabled and autistic people at an appalling rate.

To make matters worse, learning disabled and autistic people aren’t the only demographic the NHS is detaining at an alarming scale in its inpatient settings. Data obtained by the Canary reveals that, as a group more broadly, the NHS holds disabled people in detention at a significantly higher rate than non-disabled people.

However, there’s another glaring problem too. The data the NHS holds on this is enormously limited. As a result, the figures the Canary obtained are only part of the story. This is because, as it turns out, the NHS actually has no official record of the number of disabled people it holds detained under the MHA.

The latest NHS statistics on detentions continue to evidence the dire persisting institutionalisation of learning disabled and autistic people. But, in 2025, the NHS publishes absolutely no data at all on the number of disabled people it holds sectioned within its estate. In other words, to this day, there’s no way to monitor the use of MHA detentions on disabled people – and that should be a scandal.

Detentions of learning disabled and autistic patients: failing targets abysmally

In 2011, an investigation at Winterbourne View hospital blew wide open the horrifying abuse of learning disabled people in the NHS’s care. An undercover Panorama exposed their shocking treatment at the hands of care workers – of whom 11 went on to be convicted. As the BBC reported at the time, patients were:

being slapped and restrained under chairs, having their hair pulled and being held down as medication was forced into their mouths.

The victims, who had severe learning disabilities, were visibly upset and were shown screaming and shaking.

One victim was showered while fully clothed and had mouthwash poured into her eyes.

Undercover recordings showed one senior care worker at Winterbourne View asking a patient whether they wanted him to get a “cheese grater and grate your face off?”.

The abuse was so bad that one patient, who had tried to jump out of a second floor window, was then mocked by staff members.

A subsequent review of NHS services found that Winterbourne was hardly an exceptional case either. It was these appalling revelations that galvanised the NHS to start work on ending the institutionalisation of learning disabled and autistic people. Notably, in February 2015:

NHS England publicly committed to a programme of closing inappropriate and outmoded inpatient facilities and establishing stronger support in the community

And crucially, an important part of making sure it was accountable to this goal involved establishing a regular data collection. This was in order for the public, the NHS, and government to measure its progress. So, in tandem with its pledge, the NHS began officially publishing this data from February 2015. It uses March 2015 statistics as the reference point for comparison.

The plan? To reduce:

usage of inpatient provision by approximately 50% over the coming three years.

In the years since, successive governments and the NHS have reaffirmed their commitment to meeting this target as well. Notably, more recent pledges to it have included NHS England’s 2019 goal to reduce the number of learning disabled and autistic people detained on its inpatient care estate. Again, it promised to halve the number relative to 2015 levels. The target date was March 2024. What’s more, the government reaffirmed this commitment in 2022 as part of its ‘Building the right support action plan’.

The results? In March 2015 the NHS had 2,395 learning disabled and autistic people in its inpatient settings. By December 2024 – the latest month for which data is currently available – the statistics showed there were 2,050. Nearly a decade on, the NHS has made a less than 15% reduction. In short, it has utterly, abysmally failed to meet this target.

Systemic abuse in the NHS hasn’t stopped

Of course, in that time, the systemic abuse of learning disabled and autistic patients in these facilities has only continued. In 2019, another Panorama exposed the appalling psychological abuse rife at Whorlton Hall in County Durham. Following the revelations, in 2023, Teesside Crown Court convicted four members of staff the BBC caught on camera for “ill-treating” patients at the 17-bed inpatient unit.

So, here we have two exposés – eight years apart. Both reveal the unconscionable abuse of learning disabled and autistic people. But they’re hardly the only ones. Behind every one of those 2,050 is a person, who could – and likely does – have more stories of gross misuse of the MHA, and abuse under detention.

Canary journalist Nicola Jeffery’s vital reporting gave a voice to three such patients in 2024. Crucially, each were definitive accounts of just such continuing systemic abuse and overreach of the MHA. In particular, Jeffery shone a light on the detentions of three autistic women – Megan, Holly, and Saffron – all living with avoidant restrictive food-intake disorder (ARFID), alongside other conditions.

In 18 year-old Megan’s case, Jeffery described how staff at the William Fraser Clinic at Royal Edinburgh Hospital had drugged her and:

allegedly forcibly manhandled and physically assaulted her, and even called her a “spoiled brat”.

Her mum Shona recounted one especially violent incident where staff had laid on the back of her knees, crushing them. Megan has hypermobility, and had a knee injury at the time. Pictures showed her knees red and bruised after staff carried out the disgusting assault.

Technically, since Megan lives in Scotland, she wouldn’t be among the above England figures. The point is though, her story is illustrative that the endemic culture of abuse remains widespread across the NHS. Moreover, taken together, their experiences underscore how in too many cases still, NHS clinicians are weaponising the MHA against patients. Patients who simply need compassionate care and for healthcare professionals to listen to them.

Now, yet another BBC investigation at a children’s psychiatric hospital in Glasgow has once again exposed more appalling abuse. Patients between the ages of 12 to 18 described being treated “like animals” at Skye House psychiatric unit, while detained under the MHA. The report details how staff disgustingly mistreated patients, overusing physical and chemical ‘restraint’. Multiple young patients alleged staff had mocked, over-medicated, and even assaulted them. It’s more proof of the egregious endemic abuse of patients detained in NHS facilities.

Disabled patients in detentions: where’s the data?

And theirs aren’t the only stories like this the Canary has highlighted in the last year either.

The Canary’s Steve Topple has repeatedly raised the alarm over NHS hospitals holding two young women – Millie and Carla – living with myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) against their will.

Clinicians have psychologised their symptoms, in spite of the chronic systemic neuroimmune disease they both live with. As a result of this, they sectioned them under the MHA at different stages of their involuntary hospitalisations.

After Carla’s family lost the appeal against her sectioning in November, they told the Canary how doctors at West Middlesex Hospital ramped up the abuse against her. Her family had recorded evidence of “the forcefulness of staff”. A photo showed scratches from one of the nurses on Carla’s hand. Topple wrote about a video showing:

hospital staff attempting to force Carla to have her feed – despite it being too early in terms of time between feeds, as well as medication; something West Middlesex Hospital know causes Carla huge pain. At the end, one nurse forcibly removes Carla’s eye mask – something which is essential for her ME; acknowledged by NICE guidelines.

This is clearly abuse – that supposed healthcare professionals were meting out against Carla while detained under the MHA.

However, here’s the thing: nowhere in the NHS’s mental health detention records will it note the fact that Millie or Carla are disabled, let alone the specific condition they live with. They’ll be in the dataset, but nothing about their chronic health condition will show up in the NHS’s transparency releases.

This is because the NHS simply doesn’t mandate providers record this. As such, for people in disabled demographics more generally, the information is entirely non-existent. Notably, the Canary queried NHS England if this was information it holds, and if so, why it doesn’t publish this alongside the rest of its monthly statistics.

We were told that it doesn’t publish statistics “broken down by disability” and that this is because of:

data quality issues around recording of disability in the Mental Health Services Dataset which mean any data wouldn’t provide a full picture.

Higher rates of disabled patients in detention

Of course, this response also seemed to indicate that it did indeed hold some information on this, albeit incomplete. The Canary therefore made a Freedom of Information (FOI) request for the data.

This revealed that the NHS had 9,001 patients with a “record of disability” detained under the Mental Health Act. This was between 1 April 2023 and 31 March 2024. By comparison, there were 9,289 patients without a “record of disability”.

Additionally, demonstrating the inconsistency of data collection on this, the NHS’s data recorded this as ‘unknown’ for 32,147 patients.

Lack of complete data notwithstanding, the statistics give a general impression of the rates that services detain disabled people under the MHA.

For one, it shows that the NHS disproportionately holds disabled people through MHA detentions. Specifically, looking at the crude rate, we can see that the NHS detains disabled people more than four and half times the rate it does non-disabled people. This was around 20 non-disabled people per 100,000 non-disabled population, to 92 disabled people per 100,000 of the disabled population.

NHS services were also more likely to detain disabled people for slightly longer, though the disparity wasn’t especially significant. In particular, the data showed that for disabled patients, the upper quartile was 62 days in detention. It means that the NHS held around 25% of disabled patients for longer than two months. For non-disabled people, the upper quartile was 56 days – just a little short of a week less.

Obviously, the data’s incompleteness also likely makes all this a notable underestimate. It’s highly probable there are many more disabled people among the ‘unknown’ figure. However, the data we could obtain highlights two important things nonetheless.

The first is that public authorities are considerably more likely to wield the MHA against disabled people. The second is how the government and NHS doesn’t even require inpatient facilities to consistently record this. That second one is a failure of transparency – and makes it harder to hold health services to account for the first.

NHS detentions in areas with a significant disabled population

Since complete data doesn’t exist, the Canary decided to interrogate the broader Mental Health Services Data Set (MHSDS). Obviously, we couldn’t establish a more accurate rate of disabled people’s detentions under the MHA with this. However, there was still significant information we could derive from it nonetheless if we compared some data-points with other available datasets.

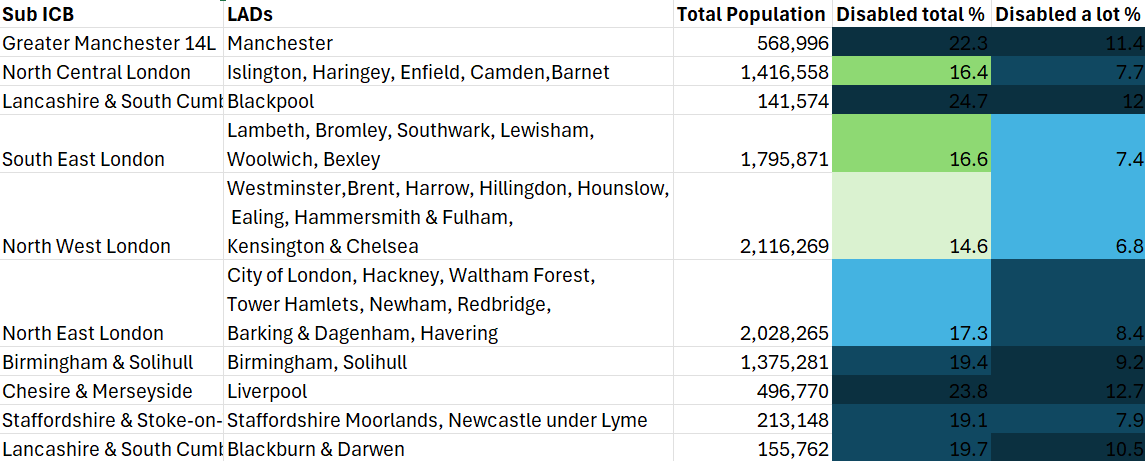

The following were the ‘top’ ten sub-ICBs with the highest rates of detention proportional to their populations:

- Greater Manchester 14L – 935 detentions (164.3 per 100,000 people)

- North Central London – 2,245 (158.5)

- Lancashire & South Cumbria – 215 (151.9)

- South East London – 2,540 (141.4)

- North West London – 2,920 (138)

- North East London – 2,705 (133.4)

- Birmingham & Solihull – 1,730 (125.8)

- Cheshire & Merseyside – 610 (122.8)

- Lancashire & South Cumbria 009 – 190 (122)

- Staffordshire & Stoke-on-Trent – 260 (122)

So, the Canary explored these locations in the context of the 2021 census’s data on disability.

The sub-ICB locations didn’t always match up completely with the census data. This is because the census uses a different area unit – Local Authority Districts (LADs). It meant that some sub-ICBs actually included a number of LADs. Therefore, the Canary tallied these up to be able to compare the data.

While most boundaries did align once we’d done this, a couple covered a slightly different area. For the most part however, these were only marginally different, so we felt they would still give us a decent approximation nonetheless.

We identified that six of the ten sub-ICBs with the highest rates of detention fell into the top two quintiles (top 20%). This means that there are proportionally more disabled people living in these ICB areas. You can see the data below for these ten sub-ICBs. The darker the shade of the cell, denotes the higher the quintile. The Canary has based these quintiles on age-standardised disabled census data for England across 309 LADs.

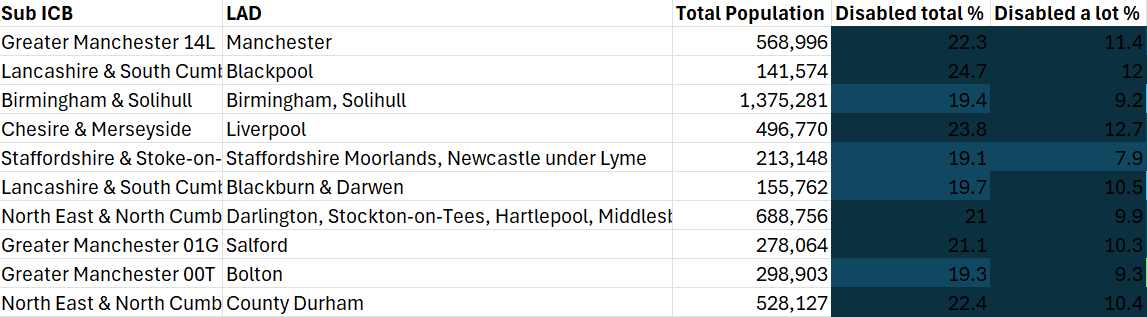

Worse than this outside London

However, as the table above demonstrates, London sub-ICBs appeared to skew the results. Notably, the London sub-ICBs each covered an area with a significantly larger population than the majority of other locations. This ranged from a little over 1.4 million people in the North Central London sub-ICB, to just over two million in the North West London Sub-ICB. With the exception of Birmingham & Solihull sub-ICB, at 1.3 million people, the rest in the top ten for MHA detentions had populations an order of magnitude smaller – all well below a million.

On this basis, the Canary also looked at the data excluding those sub-ICBs. In this instance, the sub-ICBs with the highest rates outside London all fell within the top two quintiles for the percentage of their population disabled. Similarly, all but one of these sat in the top quintile for the percentage of the population that reported they were “disabled a lot” in the 2021 census. Staffordshire & Stoke-on-Trent ICBs was the sole exception. However, it still came within the second highest quintile.

Of course, from the limited data we have on MHA detentions with regards to disability status, there’s no way of knowing completely if the NHS is more likely to detain disabled people under the MHA. However, this data comparison does show us that sub-ICBs where there’s a higher population of disabled people, and more severely disabled people more specifically, have high rates of detentions.

We obviously can’t definitively draw a causal link from this. Even so, the correlation raises questions over the potential for one. It therefore underscores a vital reason why the NHS should record and publish data on disability demographics in its statistical releases.

Intersectional injustices probable – but we have no data to properly show it

The lack of data also means the NHS doesn’t publish disability status alongside the rest of its regular output. And this brings up other problematic limitations. Significantly, we can’t cross-tabulate this with any other demographic.

In other words, it means we can’t explore whether public health authorities detain disabled people who are multiply-marginalised more frequently either. Of course, it is more than likely the case that they do.

What we do know is the following. For April 2023 to March 2024:

- Black people were the most overrepresented in MHA detentions data. The NHS held Black people in detention with a crude rate of 239. By contrast, white people turned up in the data at a crude rate of just 69.5. Essentially, the NHS detained Black people more than three times the rate it did white people.

- Similarly, authorities detained other racially minoritised demographics more frequently as well.

- The same could be said for the most deprived patients – cropping up at a crude rate of 151. This compared to just 43 for the least deprived. Again then, this meant that the most deprived citizens were overrepresented in the data, at more than three times the rate of the least deprived. Overall, the more deprived a person was under the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), the more likely they’d be detained under the MHA.

- Age was another notable factor. People between the ages of 18 to 34 were the most likely to be detained. This was at a rate of 136 per 100,000 of that age group’s population.

In short, the NHS detained young, Black, and poor people disproportionately more than other demographic groups. It’s highly plausible that disabled people from these demographics are more likely to face the threat of detentions as well.

We can glean an insight into this in the detention data of learning disabled and autistic people. In the latest data from November 2024, the NHS was detaining Black learning disabled and autistic people at more than twice the rate of white learning disabled and autistic folks.

Given that we know there are huge health inequalities and outcomes for poor, racially minoritised, and disabled communities, and how these often intersect, this is information the public should have access to in the context of MHA detentions.

Ableist abuse baked in in the NHS

Ultimately, if disabled people are overrepresented in mental health detentions as the data we do have suggests, it’s highly plausible there are more cases like Carla and Millie. That is, authorities and public health services weaponising the MHA to psychologise chronically ill and disabled patients.

Judging by what we know about the rife psychologisation of ME patients, and systemic ableism across the healthcare system, this wouldn’t be an improbable scenario. Moreover, the continued overuse and abuse of detention for learning disabled and autistic people like Megan, Holly, and Saffron, also corroborates this as a significant possibility.

To treat Carla, Millie, Megan, Holly, and Saffron’s stories as isolated incidents would be to miss the point. This is that a system and medical professionals quick to psychologise neurodivergence, physiological diseases, and conditions they do not understand, is making people in crisis the problem, rather than recognising it’s this ableist system itself which is the problem, and obtuse medical arrogance in the face of this, the crisis.

As I previously highlighted, the NHS has actually ramped up its use of so-called ‘restrictive interventions’ in inpatient units. Notably, in November 2024, staff used physical, mechanical, and chemical restraints, seclusion and segregation, against 720 learning disabled and autistic patients. This was across 7,615 separate incidences while in mental health detention.

Technically, the NHS doesn’t treat these ‘restrictive interventions’ as abuse. However, it’s hard to see how drugging someone involuntarily, using force to restrain them, handcuffing, or placing them in solitary confinement could be seen as anything other than the inhumane, abusive response to a person in extreme distress that it is.

In other words, abuse is baked into the model of detentions under the MHA. And that model interacts with the institutional ableism, classism, and racism within the healthcare system. In short, it systematically devalues disabled, poor, Black and brown lives.

No transparency, no accountability, but no one cares

Ultimately, the fact the NHS doesn’t actually publish information on any disabled people in detention is hugely problematic. It’s leaving disabled patients like Carla and Millie at the mercy of gross misapplications of the MHA. And it’s likely there are many more stories like theirs going ignored and unheard.

Crucially, without regular data, it inhibits the opportunity for broader scrutiny of this use and abuse of the MHA against disabled patients. But it seems, no one in power – be it the NHS, or government – appears to be asking vital questions about the rate of disabled people in detention. And that should really be seen for the serious scandal it is too.

Featured image via the Canary