The independent prisons’ inspector has slammed a young offenders institution for its treatment of children under its care – including disabled ones. The lengthy report on Cookham Wood has identified multiple failings, with the boss of the inspectorate telling the government it has to act. However, the situation poses bigger questions about the UK’s prison system – as this is hardly an isolated incident.

Sky News reported that:

Hundreds of homemade weapons were found at a young offender institution “rife” with violence, according to a damning report.

Cookham Wood facility in Rochester, Kent, was put into emergency measures after prison inspectors uncovered “appalling” conditions during an April visit.

BBC News, the Evening Standard, the Independent, and the Sun all ran with the violence angle. However, what all of them failed to mention was that over a third of the children were disabled or neurodiverse, nearly a fifth were refugees or asylum seekers, and nearly two-thirds had been through the care system.

Cookham Wood: failing on all counts

Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP) said in a statement that [ED: press release]:

Cookham Wood held only 77 boys at the time of inspection, whose care was being overseen by around 360 staff, including 24 senior leaders.

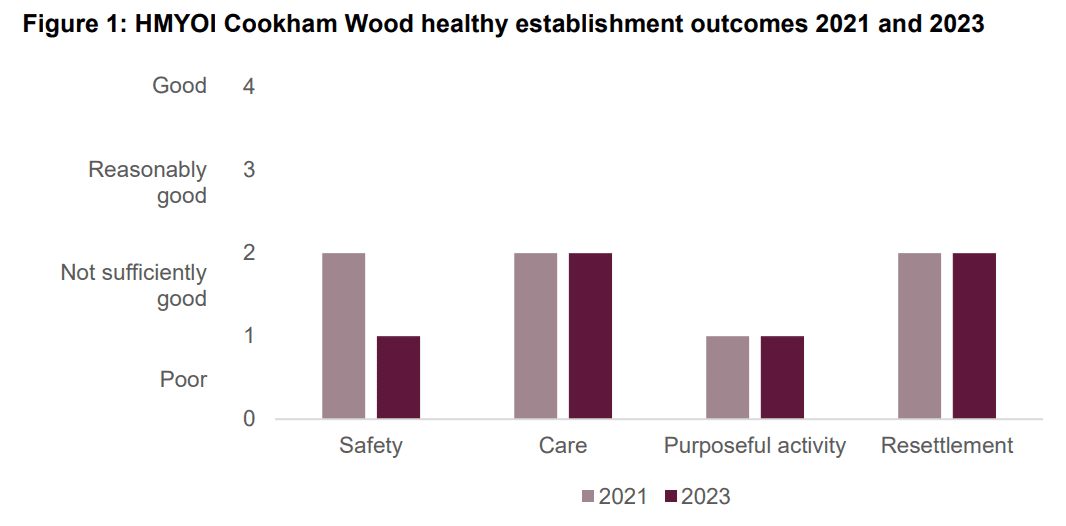

That means there are over four staff members per child. Yet staggeringly, despite this HMIP found outcomes for children were:

- poor for safety

- not sufficiently good for care

- poor for purposeful activity

- not sufficiently good for resettlement.

Despite the Youth Custody Service appointing a new governor in February, this is a stagnation, or on one measure a worsening, in conditions since HMIP last inspected Cookham Wood:

The report described that:

- Staff kept 90% of children apart from other ones.

- Staff had found more than 200 weapons in the months leading up to the inspection.

- Living units were dirty.

- Equipment was broken.

‘Hardly any meaningful human interaction’

HMIP said in a statement that:

Rather than engaging in conflict resolution, leaders had introduced extensive instructions on which boys were known to be in conflict and needed to be kept apart from each other…This undermined the provision of any meaningful regime, with access to education and other activities determined by which children could safely mix, rather than their individual needs or abilities.

Despite this, levels of violence remained high and some boys spent days on end languishing in their cells in response to incidents. During that time, most had hardly any meaningful human interaction. Other children were separated for their own protection, and inspectors met two boys who had been subjected to solitary confinement for more than 100 days because staff could not guarantee their safety.

In the report, HMIP logged even more damning findings. For example, it found:

- There had been 34 instances of self-harm in the previous six months – with two children each carrying out 10 of these incidents.

- 64% of children had been verbally abused by others; 35% subject to physical abuse.

- Children put in isolation had received, on average, less than three minutes of education per day.

- “56% of children had been verbally abused by staff, 37% had been threatened or intimidated, and 29% said they had been physically assaulted”.

- 41% of children were locked in their cells on school days, with only a 30 minute break to get food and go outside.

- Staff had cancelled 24% of all family visits for the children in the 12 months before HMIP visited.

But it’s the experience of marginalised children which is particularly damning.

Marginalised kids: hit hardest at Cookham Wood

Of Cookham Wood’s population, 21% were adults at the time of HMIP’s inspection. Moreover:

- 58% of children were on remand – that is, they had not been convicted of a crime, and might never be.

- 61% of children were from Black, Brown, or other minority ethnic backgrounds.

- 37% of children were disabled, learning disabled, or neurodiverse.

- 65% had been through the care system.

- 10% were from the Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller (GRT) community.

For the latter, their experience was much worse. The HMIP report said:

Only 17% [of disabled children] compared with 55% of other children said it was normally quiet enough to relax or sleep at night and just 22% compared with 66% that they usually spent more than two hours out of their cells on weekdays. These children would have had a range of learning disabilities or neurodiverse conditions and their poorer perceptions needed to be understood and addressed.

Then, Cookham Wood was also detaining what HMIP called 15 “foreign national children” – likely to be refugees or asylum seekers. The report said:

Services for these children had deteriorated since the previous inspection. Home Office immigration enforcement staff no longer visited for immigration surgeries, though this was mitigated in part by quarterly visits from the immigration prison team… Children with no family in the UK could have a free five-minute phone call each month and one child was using this opportunity.

However, the report failed to spell out the fact that 15 refugee or asylum-seeking children equated to just under 20% of the total number being detained.

The report, though, identified the polar opposite of the state of Cookham Wood.

Blame the bosses, not the kids

The Cedar unit is a 17-bed resettlement block, which is separate from Cookham Wood’s main building. HMIP said in its report:

The one area of strength at the establishment was Cedar unit (the resettlement/release on temporary licence unit). The unit had benefited from consistent leadership from a custodial manager with a clear vision who worked effectively with leaders in the resettlement team to implement an innovative approach to release on temporary licence for education, work and promoting family ties. Cedar unit was an oasis of calm and effective behaviour management in comparison to the rest of the establishment, and for the eight children living on the unit, it provided a potential opportunity to change their lives for the better.

It beggars belief that one part of Cookham Wood can be so different from another. However, HMIP clearly identified what the problem was: the bosses:

The newly appointed governor had been in post for about six weeks and he indicated to us that he was aware of the problems in the establishment. The leadership team, however, lacked cohesion and had failed to drive up standards. In this context we were also surprised to be told that since the governor had been appointed, no senior leader from the Youth Custody Service had visited to make their own assessment of the establishment’s evident failings.

It noted:

Many staff were open about how little confidence they had in leaders and managers. We were informed of some staffing shortfalls, but also that around 360 staff were currently employed at Cookham Wood. This included 24 senior leaders. In addition, there were several more working for partners in health care, education, and other areas.

Abolition is the only answer

HMIP concluded that:

The fact that such rich a resource was delivering such an unacceptable service to just 77 children indicated that much of it was being wasted, underused or needed reorganising to improve outcomes at the site.

The boss of HMIP Charlie Taylor said:

These findings would be deeply troubling in any prison, but given that Cookham Wood holds children, they were completely unacceptable. As a result, I had no choice but to write to the secretary of state immediately after the inspection and invoke the urgent notification process.

The other problem with Cookham Wood is that its appalling conditions and treatment of people are hardly isolated in the prison estate. As the Canary reported, HMIP recently described conditions at Eastwood Park women’s and young offenders’ prison in Bristol as “terrible” and “wholly unsuitable”. At least four people have died at the prison in the past year.

it is not just one rotten prison, or a few violent officers… The problem is the whole carceral system, which is hardwired to dehumanise and brutalise the people it imprisons.

Of course, the problem is bigger than that – it is our entire criminal justice system which is broken. When somewhere like Cookham Wood can detain children – many of them marginalised and vulnerable – in such appalling conditions, it’s a damning indictment of the prison system.

But perhaps the bigger question is, how have we, as a society, reached a point where the state is so readily imprisoning children, anyway?

Featured image via Channel 4 News – YouTube