The independent coronavirus (Covid-19) inquiry has been urged to make race a central part of its work. 26 organisations – including the NHS BME (Black and Minority Ethnic) Network, Disability Rights UK, and the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants – have written an open letter. The inquiry is set to hear evidence in June, but is currently determining which issues exactly should be examined.

Potential scandal from Covid inquiry

Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice and the Runnymede Trust put the letter together. They’re asking for ethnic minority communities to be at the centre of the inquiry. They state:

We are concerned by the announcement during the latest hearing of the COVID-19 Inquiry that structural racism will not be explicitly considered in Module 1, despite multiple requests for the Inquiry to interrogate why Black and minority ethnic people contracted and died from COVID-19 at such starkly disproportionate rates.

The very idea that the inquiry might not consider race as central to its work is scandalous. During the early stages of the pandemic, Black and Asian people had higher rates of death than white people. The British Medical Journal (BMJ) explained that:

The groups at greatest risk have also changed over time: at the start of the pandemic, covid-19 mortality was highest in the Black African group,1 whereas in subsequent waves it was highest in Bangladeshi and Pakistani groups.2

In the most recent wave to December 2021, only Pakistani men and Bangladeshi men and women experienced excess mortality compared with the White British group after adjustment for sociodemographic and health factors and vaccination status.

As more communities are now vaccinated, the latest data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) shows that the ethnic minority death gap has now closed.

Inequality writ large

That said, the initial spikes of disproportionate deaths of ethnic minorities cannot be forgotten. The open letter from campaigners argues that:

COVID-19 is not just a health crisis; it’s also a social and economic crisis. The ability to cope, to protect and to shield oneself from the virus varies vastly for people from different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds.

These inequalities are certainly not new, but instead are amplified by the scale of the ongoing pandemic. Shockingly, the open letter notes that the government appears to have bypassed its responsibility towards ethnic minorities, once again:

We are disheartened to learn that the Listening Exercise has been outsourced to PR companies with close ties to Government as part of an entirely separate process to the Inquiry itself. Any inquiry must place the voices of those worst affected at its core; we expect the COVID-19 Inquiry to set up accessible consultations directly with minority ethnic communities and their representatives, to listen and then act upon their experiences.

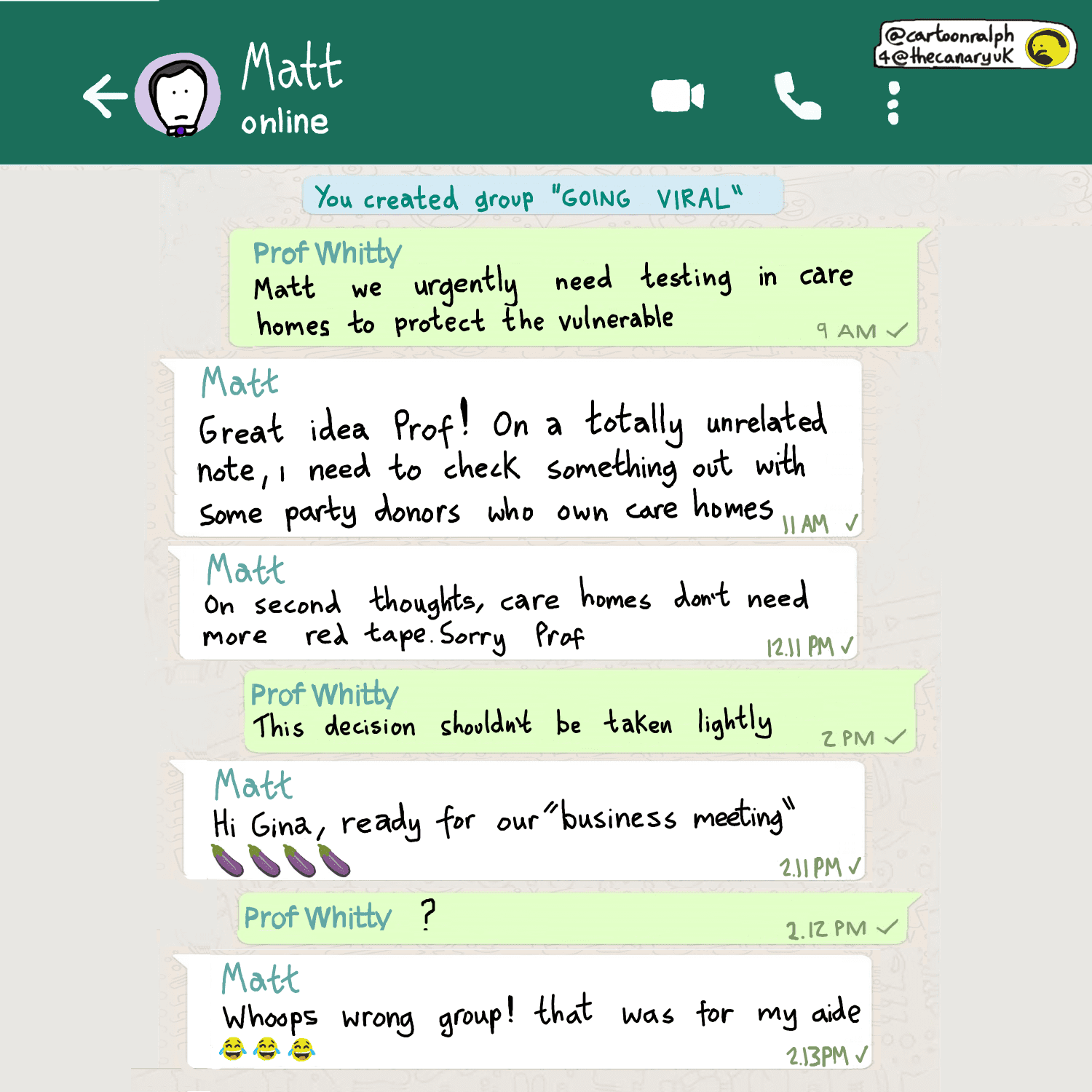

The fact that the government, even during a Covid inquiry, is turning to private outsourcing is beyond belief. The pandemic was rife with government cronyism – as the Canary‘s Tom Coburg explained:

The provision of PPE (personal protective equipment) and Coronavirus (Covid-19) related contracts reveal a pattern that suggests, at best, government incompetency and, at worst, cronyism.

Cronyism is so central to the government that one barrister has reportedly warned it to limit the information it shares with the inquiry.

Medical racism

Communities of colour have disproportionately been impacted by Covid. However, that’s not the whole story. It should be obvious for the inquiry to consider the inequalities compounded by Covid. Somehow, though, that’s not a given. On top of that, statistics regularly ignore disabled people of colour. They’re so often left behind by data that when it comes to reviewing health responses they’re barely part of the conversation.

In an investigation from 2020, the Canary spoke to Sarah Chander, a senior policy advisor at European Digital Rights, who told us:

In a world of deep, sustained inequalities, our default understanding must be that data, technologies and systems deigned to record, study and classify marginalised communities are flawed. They reflect the power imbalances of today and of history. In such a context, claims of neutrality are also political statements, ones which seek to derail from a more cohesive understanding of structures of oppression and historical imbalances.

If the Covid inquiry was to have any hope of bringing justice for bereaved families and communities, it would respond on multiple levels. It would listen to the 26 organisations urging it to put race at the centre of its work. Then, it would take the deaths of people of colour from the pandemic seriously. It would incorporate class and poverty analysis into its work with race. Moreover, it would also consider how incomplete data needs to be combined with listening to people of colour about their experiences.

If the inquiry chooses not to do any of this then people of colour will know everything they need to know about its position on their communities that were severely damaged by the pandemic.

Featured image by Unsplash/Noah Matteo