A new UN science report is set to send what may be the starkest warning yet about the impacts of climate change on people and the planet.

The assessment is the second in a series of three reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The reports make up the latest review of climate science; this takes place every six or seven years for governments.

‘Code red for humanity’

It’s being published on Monday 28 February. That’s a little over 100 days after the Cop26 summit agreed to increase action to try and limit global warming to 1.5C (2.7F). Doing so is essential in order to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

Conference president Alok Sharma described the outcomes of the UN talks in Glasgow as keeping the temperature goal alive, but only with a weak pulse.

The first in the series of reports was released last summer before Cop26. At the time, UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres described it as a “code red for humanity”. It set out the unequivocal and unprecedented impact humans were having on the planet.

This latest assessment is expected to be even more worrying. It looks at the impacts of climate change, efforts to adapt to rising temperatures, and vulnerabilities.

Tipping points

A draft leaked in 2021 warned of the risk of crossing dangerous thresholds or “tipping points”. This is where things such as melting of ice sheets or permafrost, or rainforests becoming grassland, become irreversible, with huge consequences.

The final version of the study will be released after its summary was approved after some haggling in a process involving representatives of governments and scientists. It means that governments have signed off on the findings of the final version.

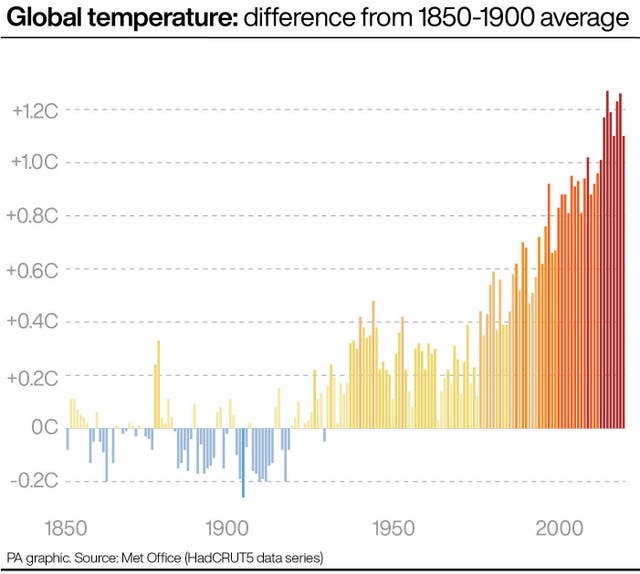

The report will set out the impacts of rising temperatures, which have already reached 1.1C (1.98F) above pre-industrial levels, from droughts to floods, storms, effects on health, agriculture and cities, and cascading and irreversible impacts.

There will be a specific focus on the different regions of the world, as well as looking at vulnerable populations and communities, migration and displacement. It will detail options for – and limits to – adapting to climate change.

‘A grim vision’

Mark Watts is executive director of the C40 Cities group of mayors taking action on climate change. Ahead of publication, he warned the latest report was likely to “paint a grim vision” for big cities from London to Lima:

City residents are already on the front line of a worsening vulnerability to climate impacts such as deadly flooding, sea-level rise, wild fires, extreme storms and unbearable urban heat.

It is clear we are now in the climate crisis, not waiting for it. We can still overcome climate breakdown and build a thriving future, but urban adaptation efforts must outpace this new climate reality.

He said national leaders must work with mayors to invest in cities’ defences. And richer countries must deliver on finance commitments to poorer nations to ensure no city is left behind.

A crisis that ‘demands a global response’

Former UK chief scientist David King warned that because of the way the IPCC reports worked, they didn’t include the most up-to-date studies or evidence. For example, these could include heatwaves in Canada and floods in Europe in 2021. King founded the Climate Crisis Advisory Group of independent experts.

He said the importance of the reports could not be overstated, telling the PA news agency:

This crisis is such that it demands a global response.

Whereas the Covid-19 outbreak has been cataclysmic for the world, nevertheless we do recover from these as we know from the past, even before we had vaccines, we had plagues and we recovered from them as a humanity.

There’s absolutely no guarantee that we will recover from the impacts of climate change, unless we all begin to work together and far more quickly, far more effectively, than we are doing at the moment.

There’s a real cause to say the climate crisis is with us and we all have to work together and deal with it in an equitable way.

He warned:

Each individual nation is run by governments that are working for their own communities and that kind of selfishness doesn’t fit this challenge.

We all have to understand this is a joint challenge – and I think we’re quite a bit removed from that as we stand now.