The UK announced that it had secured the support of 45 governments “in new pledges to protect nature” at COP26 on 6 November. A number of these promises focused on agriculture and how to make farming more “sustainable for the future”.

Many civil society and small farmer-focused organisations argue that agroecology is key to truly sustainable farming. This is the practice of cooperating with nature to yield agricultural produce, rather than using artificial inputs like pesticides and fertilisers. It’s an ecological, not a technological, approach.

But the word agroecology doesn’t feature in the UK government’s announcement on the nature-focused pledges. And that wasn’t the only omission either.

Not an outlier

As the University of California’s Miguel A Altieri explained in a report titled Agroecology: The Bold Future of Farming in Africa:

Agroecology is deeply rooted in the ecological rationale of traditional small-scale agriculture, representing long established examples of successful agricultural systems characterized by a tremendous diversity of domesticated crop and animal species maintained and enhanced by ingenuous soil, water and biodiversity management regimes, nourished by complex traditional knowledge systems.

It is, in a nutshell, an approach that works with and harnesses local ecosystems to produce food that’s fitting for – and benefits – the environment its grown or produced in. It largely shuns artificial and damaging inputs like pesticides and fertilisers. And it’s already practised by many small-scale farmers around the world.

Beyond the “new pledges to protect nature”, the membership organisation Climate Land Ambition and Rights Alliance (CLARA) highlighted that the word agroecology has also been missing elsewhere during the COP26 negotiations.

The UN describes the Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture – the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change’s (UNFCCC) only programme that focuses on agriculture – as a “landmark decision” that “recognizes the unique potential of agriculture in tackling climate change”. Co-facilitators have put forward draft conclusions during COP26. CLARA pointed out on 5 November that the different versions on offer at that point talked about taking into account “the diversity of agricultural and ecological systems”, sustainability, climate-resilience, and “integrated systems” approaches. But it said none mentioned the word agroecology. The organisation raised the question:

Who’s afraid of the term ‘agroecology’? Why the heavy resistance?

No inputs? Heaven forbid

Nigerian environmental justice advocate, poet, and author Nnimmo Bassey told The Canary at COP26 that the omission isn’t surprising. He said that the UN’s system in relation to agriculture has been “contradictory”. He gave the example of the body characterising plantations – areas where a single tree species or other cash crops are grown – as forests.

As academics have previously pointed out, monoculture (single species) plantations are hugely inferior to diverse forests in terms of storing carbon. Plantations are also terrible for biodiversity.

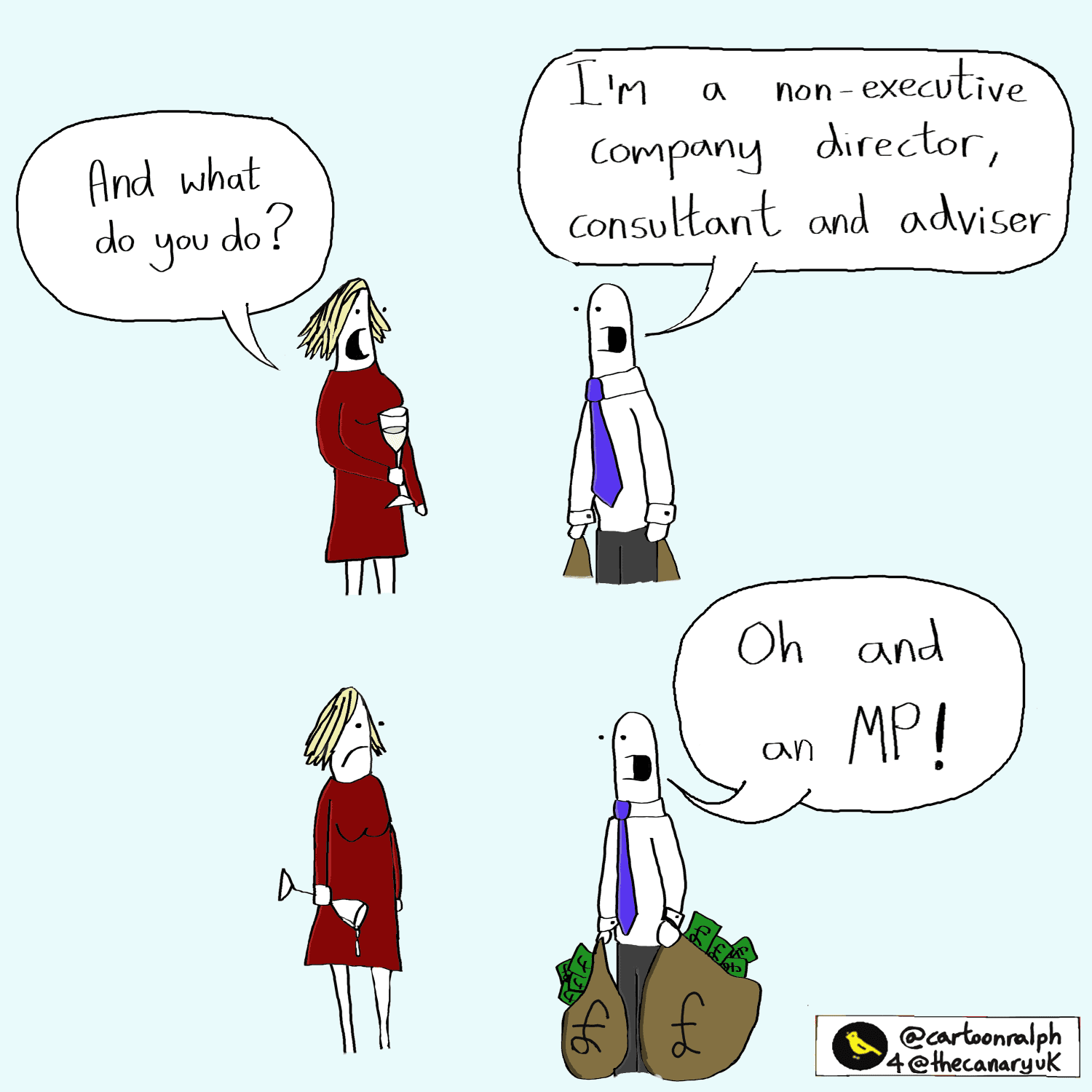

Bassey highlighted that “agroecology would not tolerate” the artificial inputs that the current corporate-led and globalised system of agriculture demands. This of course threatens the interests of big business who profit from those inputs. And Bassey says that such corporations have an “overbearing influence” over the negotiations at events like COP26.

He also asserted that in some countries, these artificial inputs are “political tools” and governments may resist supporting practices like agroecology, which would benefit the majority of farmers, due to the “political clout” that big agriculture has. However, Bassey suggested that eventually, hopefully, governments may “come around to” agroecology.

No one size fits all

The UK government argues that it has recognised the potential of agroecology, both inside and outside of COP26.

When asked by The Canary about the lack of the word in its pledges announcement, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) pointed to the COP26 “Policy Dialogue” on the transition to sustainable agriculture and the “Policy Action Agenda“. The former includes one reference to “agro-ecological approaches”, in relation to where countries could direct investment. The policy action agenda doesn’t mention the word, either in its “principles” of what constitutes sustainable agriculture or elsewhere. It does, however, concede that artificial inputs can be detrimental to the climate and environment. A Defra spokesperson also said:

To keep 1.5 degrees alive, we need action from every part of society, including an urgent transformation in the way we manage ecosystems and grow, produce and consume food on a global scale.

The UK government is leading the way through our new agricultural system in England, which will incentivise farmers to farm more sustainably, create space for nature on their land and reduce carbon emissions.

Defra further asserted that the government has avoided being “prescriptive” about sustainable agriculture, in order to recognise that “that there is no one size fits all”.

One corporate size for all

But the agricultural pledges suggest that a ‘one size fits all’ is, in practice, dominating the corporate-heavy COP26 approach. That’s despite the UK’s environment secretary promising that “farmers, indigenous people and local communities” will play “a central role in these plans”.

In its announcement on 6 November, the UK asserted that billions of public money will fund “agricultural innovation” in pursuit of “sustainable agriculture”. It seems these innovations are heavily rooted in technology and include the creation of “new” crop and livestock “varieties”, aspects of agriculture that are dominated by corporations. Meanwhile, the Policy Action Agenda’s list of ‘allies’ includes some of the biggest agricultural chemical and seed names in the business, including Syngenta and Bayer (a company that merged with Monsanto).

In short, the COP26 proposals and plans, with their talk of ‘innovation gaps’ and “technology development”, largely sound like the “technofix mess” that small farmer-focused organisations and advocates have long-criticised.

That criticism stems from the fact that the corporate-led, industrial agriculture system imposed on people around the world after the second world war has been a recipe for disaster in terms of the climate and biodiversity. Moreover, it has stripped farmers of their sovereignty over seeds, lands, and food.

Notably, the phrase food sovereignty was also missing from the “new pledges to protect nature” announcement and related policy documents.

Corporate-capture

Many have criticised COP26 for the corporate capture on display, particularly in relation to its fixation on what many argue are false solutions and its shielding of the fossil fuel industry. But the reach of corporations is wide, and it continues to strangle real progress on many issues at the conference.

The agricultural pledges, with their absence of focus on agroecology, food sovereignty, and indeed no mention of curtailing the industrial meat and dairy industry, have got corporations’ fingerprints all over them.

Featured image via Ivan Radic / Flickr