A report has raised human rights concerns regarding decades of failed government privatisation in the UK. A campaign group said it identified potentially ‘serious human rights breaches’. And one of its authors, former UN investigator Philip Alston, is no stranger to criticising UK political agendas. Indeed, it was Alston who wrote a damning report on poverty in the country in 2018.

“Public Transport, Private Profit”

Alston is the former special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights. His 2018 report was scathing in its criticism of the UK government. Now, he’s helped put together another damning assessment.

The new report is called Public Transport, Private Profit: The Human Cost of Privatizing Buses in the United Kingdom. It looks at the state of bus services across the UK since Margaret Thatcher’s government privatised them in 1985. Alston co-authored the report with Bassam Khawaja and Rebecca Riddell. They are co-directors of the Human Rights and Privatization Project at New York University’s Center for Human Rights and Global Justice. They’ve pulled together facts and figures and collected testimony from passengers across the country.

Alston: a “master class in how not to run” a public service

Overall, Alston said of UK bus services:

Over the past 35 years, deregulation has provided a master class in how not to run an essential public service, leaving residents at the mercy of private actors who have total discretion over how to run a bus route, or whether to run one at all.

In case after case, service that was once dependable, convenient, and widely-used has been scaled back dramatically or made unaffordable.

The absence of a strong public bus system affects a great many people’s economic opportunities, but also their means to participate in their communities, travel to football matches or libraries, and visit family and friends.

These comments were just the tip of the iceberg. Because the report itself detailed how the UK’s bus network is failing the poorest people the most.

Spiralling financial chaos

There are overarching problems with the services. For example:

- Average bus fares have risen by 403% since 1987. Yet the government has frozen fuel duty on cars for the past 11 years.

- Prior to 2013, bus companies made an average profit of £297m a year. But they only reinvested between 0.2-1.5% of turnover into services.

- As of 2019, the public was paying for 42% of funding for bus services in England, to the tune of £2bn a year.

- Since 2009, local authorities have cut more than 3,000 bus routes in England which they were subsidising.

The end result of all this? A service that’s falling apart.

Unreliable

As the report summed up:

Deregulation has failed to provide a reliable bus service. Passengers said buses were frequently late, did not show up at all, or often broke down.

The report didn’t document the statistics for bus punctuality and reliability. But the latest government figures show:

- “Frequent” bus services in England were on average 1.7 minutes late in 2018/19.

- This lateness varied across local authorities. For example, in Gloucestershire it was 6.1 minutes. A lot of local authorities did not report their data.

- Meanwhile, “non-frequent” bus services in England (outside London) were only on time 83.5% of the time in 2018/19.

- Again, the local authority figures for this varied. For example, in Leicestershire only 63% of non-frequent services ran on time.

The report was clear on where the blame lies for this run-down industry.

Disastrous deregulation

It said that:

Deregulation has made it impossible to run the type of integrated network of services that is taken for granted in many countries around the world. The government argued in 1984 that a free-market approach would outperform an integrated, regulated system, confidently predicting that “informal measures of co-operation between operators will develop to ensure that their services connect. But deregulation of bus transport has led to a deeply fragmented system that would shock those not accustomed to it: multiple private bus operators competing in the same areas and sometimes on the same routes, timetables that do not line up between operators or other modes of transportation, and multiple ticketing options that add needless complication to bus journeys.

So, what is the effect on passengers?

Passengers at the sharp end

The report found multiple failures in bus services for passengers. For example:

- Between 1982 and 2016/2017, passenger journeys on local bus services dropped by 38% in England (outside London), 45% in Wales, and 43% in Scotland. Yet under the government-regulated Transport for London in the capital, they rose by 89%.

- A 2012 study found that 19% of workers turned down a job offer because of “the quality of bus service”.

- Almost 300,000 children cannot reach a secondary school within 30 minutes using public transport.

- Less than 50% of rural households live within a “13-minute walk of an hourly bus service”.

- By 2019, over 3 million people couldn’t “reach any food stores within 15 minutes by public transport”.

And bus privatisation has hit poor and disabled people the hardest.

Poor people

The report noted that around 40% of “low-income” people don’t have a car. Yet as it said:

those on lower incomes take the highest number of bus trips.

Such individuals can face severe barriers to public transport and are heavily impacted by rising costs and service cuts. They often have worse bus access, may not be able to afford it, work non-standard hours, and are more likely to rely on the bus as their only option. An inability to afford transportation can prevent people from accessing necessary services, limit access to work, reduce quality of life, increase health inequalities, and lead to social isolation.

Disabled people

For chronically ill and disabled people, the law says buses have to have at least one wheelchair space. But this doesn’t mean buses are fully accessible. A 2019 report found numerous barriers for chronically ill and disabled people in London. These included:

- Ramps not working.

- Bus drivers prioritising pushchairs over wheelchairs.

- Some buses only having one wheelchair space.

Also, up until last year, the government had not made accessibility a legal requirement on rail replacement bus services. Figures showed that six out of 10 of the vehicles train operators used did not comply with accessibility requirements. Moreover, England’s disabled person’s free bus pass only permits off-peak travel. So if chronically ill and disabled people want to travel at busier times of the day, they have to pay. In 2019, only 60% of disabled people in England (excluding London) were happy with bus services.

So, what is the government doing?

Tinkering around the edges

The report noted that the government’s:

2021 bus strategy for England doubles down on the role of private companies to deliver a public service, without addressing the reasons they have failed in the past or meaningfully expanding options for public ownership and control.

The proposed reforms do little more than tinker with the existing system. The strategy does not commit the government to legalizing new municipal bus companies or removing the severe barriers to achieving bus regulation that local authorities face. It does not address power imbalances between local transportation authorities and bus operators. And it does not impose an obligation on local authorities to provide a minimal service, leaving the core of the deregulated system fully in place.

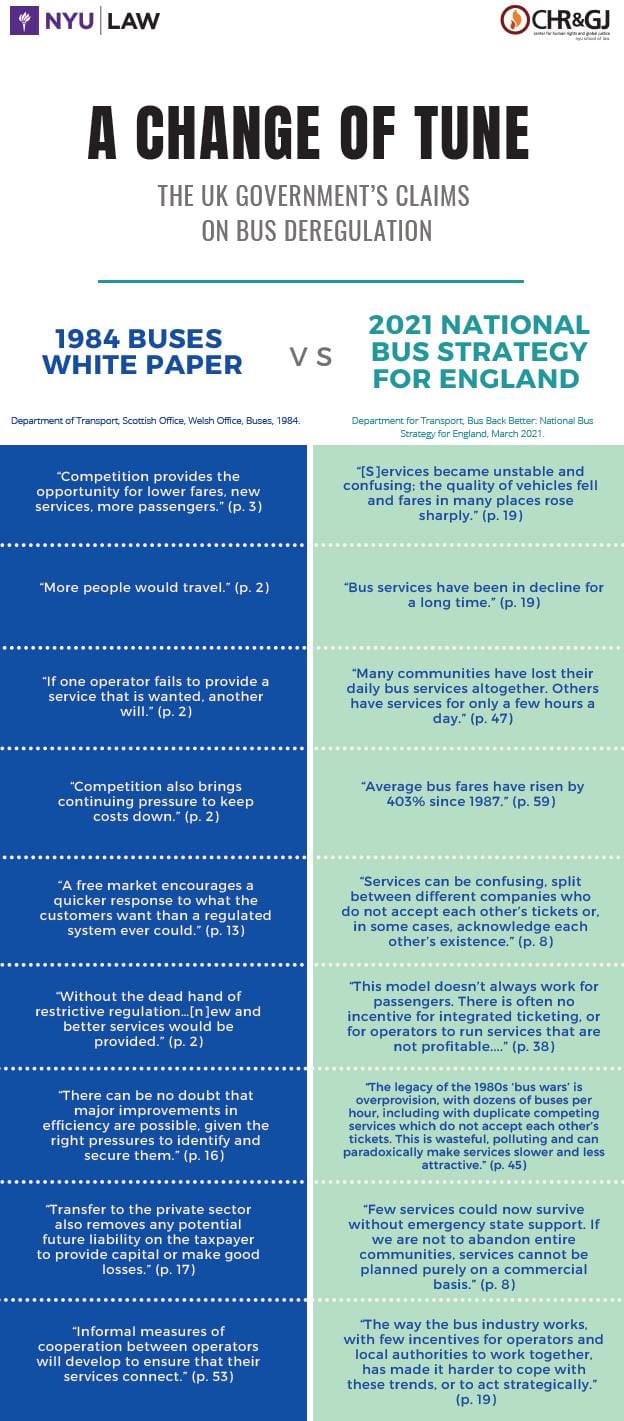

The report also compared the aims of bus privatisation according to Thatcher’s government with what the UK government now says about it. This essentially shows the government admitting that privatisation has failed:

The UK government says…

The government disagreed with the report’s conclusions. As the Guardian reported, a spokesperson for the Department for Transport said the new bus strategy would “completely overhaul services”, and:

Services across England are patchy, and it’s frankly not good enough.

They added:

We will provide unprecedented funding, but we need councils to work closely with operators, and the government, to develop the services of the future.

The report recommends…

The report said [pdf, p37] the government should:

- “Embrace public control of bus transport.”

- “Guarantee access to public transport.”

- “Support local authorities.”

- “Ensure affordability.”

- “Combat climate change with a strong bus system.”

But overall, it seems that little is going to change. This is despite the UN already expressing concerns over the UK’s public transport system. And as the report notes, it’s not just the detailed issues around bus services which are the problem here.

A human rights issue?

The report states that:

There is currently no right to a minimum level of public transportation set out in UK law or policy. And public transportation is not traditionally regarded as a right in and of itself. Yet it is abundantly clear that lack of transportation has severe impacts on people’s ability to live a decent and fulfilling life, including their access to work, education, healthcare, and food.

It also noted:

The privatization of public transportation raises significant human rights concerns. There is a strong case to be made that human rights law requires States to directly provide public services or ensure the provision of public services by a public body where the service is essential for realizing one’s rights—and that increased privatization of rights-related services undermines human rights.

“Serious” human rights “breaches”

Emily Yates from the campaign group the Association of British Commuters said:

There is only one conclusion to take from this report – the government must urgently amend bus legislation and provide proper support to councils to move towards public control and ownership. There are now just months left before England’s National Bus Strategy locks us into bus deregulation for another generation. Failure to act will leave the UK on the wrong side of history – and the government in serious breach of its human rights obligations.

So, as Alston summed up:

The United Kingdom is one of the wealthiest countries in the world, and can afford a world-class bus system if it chooses to prioritise and fund it. Instead, the government has outsourced responsibility for a vital public service, propping up an arrangement that prioritises private profits and denying the public a decent bus.

Given the UK government previously ignored UN reports into its human rights violations against chronically ill and disabled people, it will probably not heed this report’s findings. But Alston and the team’s report provides a valuable and much-needed insight into the state of bus provision in the UK. It’s one that campaign groups and trade unions can use to drive the narrative around our public transport system forward. And hopefully, the report will lead to change in the future.

Watch the launch event for the report below:

Featured image via Bassam Khawaja