Horrific news hit the front pages on Saturday when 102 peace activists were murdered (and around 500 more injured) in Turkey’s capital city by two suicide bombers apparently connected with Daesh. The victims had been on their way to an anti-war rally when the attack occurred, and included “teenage activists,” a “nine-year-old boy,” “candidates for parliament” and “a 70-year-old grandmother.”

In the wake of the bombing, the progressive HDP party insisted there had been “no police around the crime scene when the explosion occurred” and that, when they finally arrived, they attacked “the people who intended to help injured people” with “tear gas bombs.” In fact, protesters claimed that police had tried to prevent ambulances from reaching the wounded until protesters beat them out of the way. Responding to these events, HDP deputy Ertuğrul Kürkçü asked: “who could doubt that this is [the] work of the Palace?” And one murdered activist had tweeted something similar just before the march began, saying: “the Palace (Erdogan) wants war, we people want PEACE.”

Soon afterwards, around 10,000 people came out into the streets of Istanbul as part of impromptu protests that blamed the government for the massacre. Thousands more protested in the capital itself, where shouts of “thief and murderer, Erdoğan” could be heard. The slogan Katil Devlet, or ‘murderer state’, was commonplace in each demonstration and dozens were arrested. At the same time, voices of solidarity could be heard in London, Germany, France and Belgium.

In the context of President Erdoğan’s destruction of the country’s peace process, his crackdown on progressives and the state’s murder of more than 100 civilians since late July, HDP co-chair Selahattin Demirtaş insisted that Turkish progressives were “facing a state mindset” that had become “a mafia, murderer and a serial killer.” He also asked: “Is it possible for a state, whose intelligence organisation is [so] powerful, to not have any information on this incident?” On Twitter, @Hevallo also asked how, in supposedly the “most secure site of Turkey” (close to the intelligence, judiciary and security HQs), terrorists had managed to attack a demonstration with such ease. Others critical of the AKP regime demanded an independent investigation, as after six anti-HDP massacres and 531 deaths, zero government resignations had come and no perpetrators had been brought to justice.

According to Teneo Intelligence’s Wolfango Piccoli, there were suspicions that the State had allowed the massacre to occur in order “to scare voters into supporting Erdogan’s law-and-order, security-first platform” in the upcoming November elections. Security experts Mehmet Özcan and Ercan Taştekin, meanwhile, spoke about how “a major intelligence gap” had formed “in the police department following the politically-motivated purges” of December 2013, and about how, if previous bombings in Suruç and Amed “had been illuminated”, the Ankara blast “wouldn’t have happened”. Indeed, ANF soon noted that “the names and photographs of the two main suspects… had appeared on the list of 16 suicide bomber suspects given to police two months [previously]”, just as claims emerged that the culprit could have been the “brother of [a] terrorist involved in [a] previous atrocity”. At the same time, the Rojava Report argued that the State had “prior knowledge” of the attacks.

Meanwhile, the ruling Turkish regime continued with its routine of repressing the independent media, imposing “a broadcast ban” on images related to the Ankara Bombing, just as Twitter users reported “access issues” (a frequent occurrence in Turkey due to Erdoğan’s hostility towards Twitter activists). What followed subsequently was a state propaganda offensive, with the government declaring “3-days mourning not only for [the] 128 victims of [the] bomb blast, but also for killed village guards, police, [and] soldiers,” in an attempt to equate non-violent peace activists with armed forces involved in a very controversial and divisive war. Then, AKP minister Veysel Eroğlu tried to blame the organisers of the peace rally for the bombing, insisting they were “provocateurs” who had organised “terrorist demonstrations in order to incite discord in social harmony.”

The HDP hit back at regime attempts to claim the massacre had been an attack on the “state and national unity,” though, insisting that it had in reality been “perpetrated by the state against the people.” On Twitter, @dijraberi echoed these sentiments, emphasising that no terrorist attacks had been aimed at Erdoğan or his supporters and had only targeted “the promising, rising stars of Turkey’s politics: The Kurds and Turkish leftist allies.” For the HDP, it had been the “AKP’s policy of relying on radical groups [i.e. “ISIS, Al-Nusra, and Ahrar Al-Sham”] as proxies” in Syria that had been “at the heart” of the tragedy.

The Ankara Massacre almost certainly occurred as an attempt to stop the PKK from declaring a ceasefire, and its planners were probably surprised when the left-wing party declared it would “avoid conducting planned actions” against regime forces, other than in cases of self-defence. Nonetheless, the group did assert that the attacks in Ankara were “a conspiracy conducted by the AKP government to remain in power” and to “eliminate all the opposition circles one by one.”

Although the CHP (the biggest mainstream opposition to the AKP) also lost some young members in the terrorist attack, calling subsequently on ministers responsible for the failures that facilitated the attack to resign, the fact was that the bombing was primarily an attack on the progressive Kurdish movement represented by the HDP. Its purpose, meanwhile, was clearly to “further inflame relations between the state and Turkey’s Kurdish groups” and “stoke polarisation and violence,” which, according to the Washington Institute’s Soner Cagaptay, could only benefit Daesh.

Since the ceasefire between the PKK and the state began at the end of 2012, an environment much more conducive to the development of democracy was created, after decades of oppressive military rule and internal conflicts. This process enabled the unification of Turkish and Kurdish left-wingers around the HDP, which began to show seeds of success in this June’s elections. With more opportunities to organise and speak freely without wartime tensions and fears, people’s voices were finally beginning to be heard. The AKP’s increasing crackdown on internal dissent, hostility to the Rojava Revolution and support for jihadists in Syria, however, aided the growth of Daesh-inspired terrorist cells in Turkey, along with their attacks against the increasingly popular left-wing movement seeking to democratise the country.

Overall, Saturday’s massacre highlighted once again that “the West’s key frontline ally in the battle against Isis” was in fact the power that had proven itself least interested in protecting its own citizens from the group and its sympathisers in Turkey. Furthermore, the attack was far from an attack on Turkey as a whole, but was a clear attack on intellectuals, progressives and young activists who would be crucial for the construction of a functioning democratic society in the country. In a context of imprisonment and persecution of left-wing activists, media censorship, and propaganda and military assaults against the PKK, then, the hopes of building democracy in Turkey were essentially being killed off in their infancy by Erdoğan and the AKP.

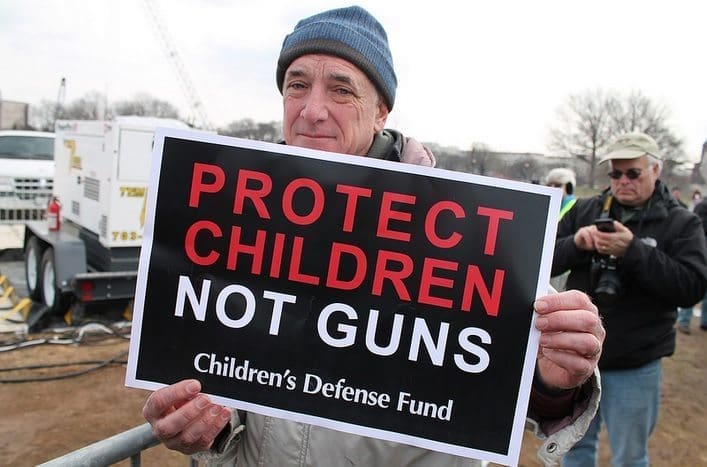

Featured image via DIHA.