A decade of reform by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) has just been linked to a “considerable” and “harmful” “impact” on the mental health of some claimants. The research behind it should spark a wider debate on the DWP’s broader agenda.

A decade of DWP reform

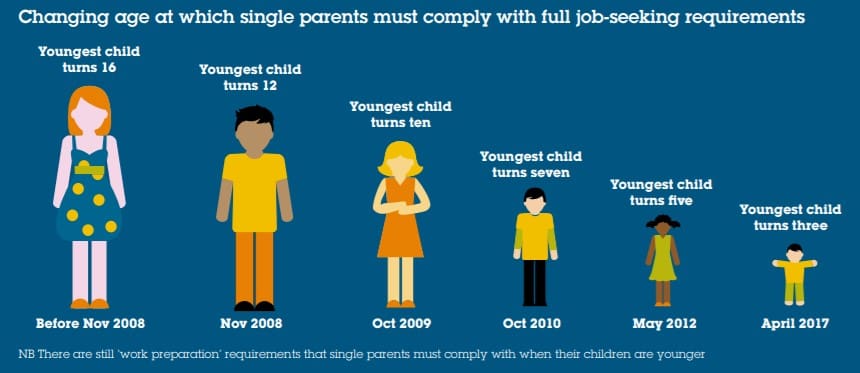

A study by Glasgow university has found a direct link between DWP reforms that affect lone mothers and worsening mental health. Its study, using data from 40,000 UK households, was analysing changes to the age at which a child had to be for the mother to not be subject to the DWP’s ‘welfare conditionality’ and job-seeking requirements. Conditionality is when welfare claimants have certain commitments to the DWP, like job searches, otherwise it will sanction (stop or reduce) their payments.

The lone parent charity Gingerbread summed up [pdf, p8] the DWP’s welfare changes:

As Glasgow Live noted:

Since 2008, when entitlement to income support was dropped for lone parents whose youngest child was 12 or older, this age been reduced from to seven and then to five.

Lone parents affected can claim jobseeker’s allowance instead of income support, but to qualify must prove they are looking for work.

Essentially, most single mothers on benefits now have to look for work whether they want to or not. Glasgow university found that the mental health of lone mothers affected by this worsened. It noted:

a decline in the mental health of affected single mothers, but no apparent effects on their physical health.

Nothing new under the sun

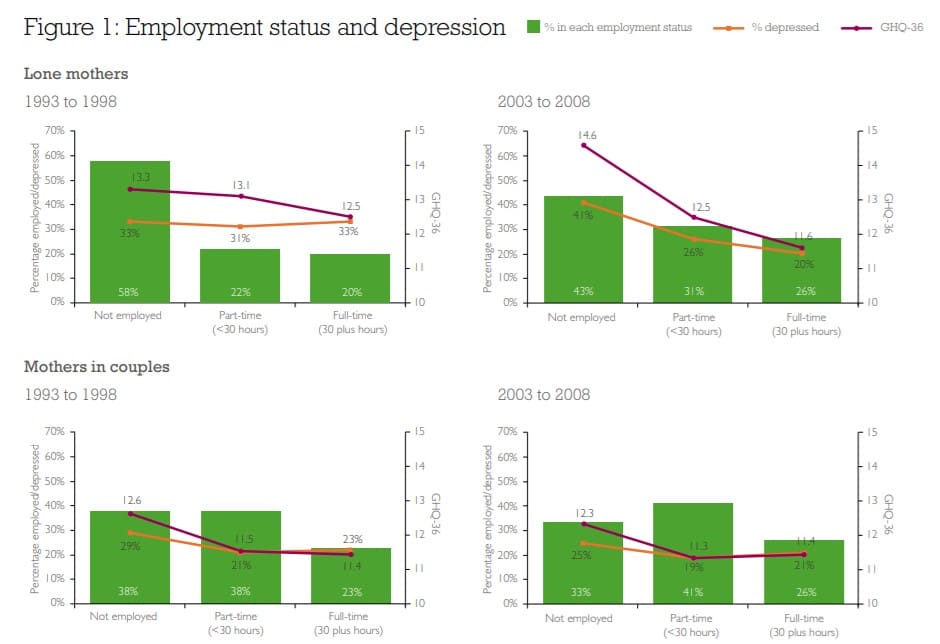

The Nuffield Foundation had already highlighted [pdf, p9] the historical increase in rates of depression among unemployed lone mothers, and the generally higher rates for all lone mothers compared to partnered ones:

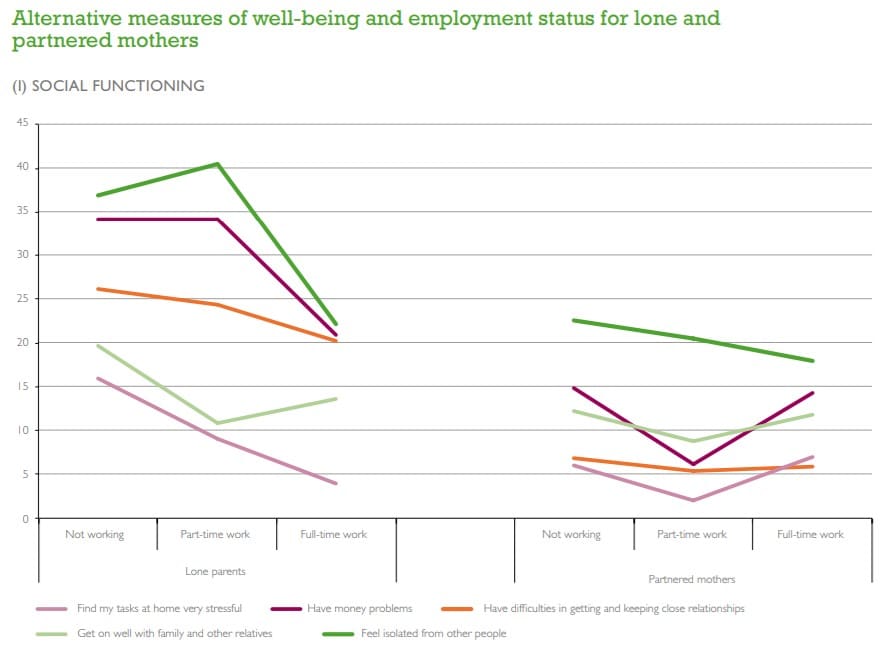

It also noted [pdf, p21] the worsening of nearly all measures of lone mothers’ wellbeing compared to partnered ones:

Gingerbread has repeatedly noted the links between DWP sanctions and poor mental health. Mental health issues among unemployed lone mothers may be increasing. But so too has the number of lone parents in work.

Work, work, work

The employment rate for lone parents has increased by 23.8 percentage points since quarter two of 1996. It was 43.8% then and 67.6% in quarter one of 2018 [xls, rows 14/57, column D].

At the same time, the relative poverty rate for lone-parent children has fallen. In 1994/95, it was 43%; in 2016/17, it was 27% [xls, table 4_14ts, row 12, columns C/Y], although this figure has been rising since 2014/15.

For unemployed lone parents, the rate of relative child poverty remained high at 44% in 2016/17. This is an increase of 11 percentage points since 2010/11 [xls, table 4_14ts, row 15, column Y/S].

But is pushing lone parents into work really the answer? What these figures don’t measure is the effect of work on both the parent and child/children.

Precarious and low paid

The charity Working Families found in a 2018 study that [pdf, p5]:

single mothers with dependent children were more likely to work in low skilled jobs such as cleaning and catering than mothers living in couple households. More than 14 per cent of single mothers were employed in low-skilled occupations, compared with eight per cent of mothers in a couple relationship. 40 per cent of mothers in a couple relationship worked in higher skilled occupations like nursing or teaching, compared with 17 per cent of single mothers.

In other words, many lone mothers were in precarious, low-paid employment.

Time poverty

‘Time poverty’ is another issue. That’s when people have less and less time to do anything but work. This is not well-researched, but as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) noted in 2008:

Around half… of lone parents are not in a position to generate sufficient income to be above an income poverty line while still meeting basic obligations (for example, to ensure their children are looked after, by themselves or someone else), however long or hard they work…

the government’s welfare reform and child-poverty agendas risk freeing lone parents from income poverty only at the price of deepening their existing time poverty. This is unlikely to improve children’s well-being.

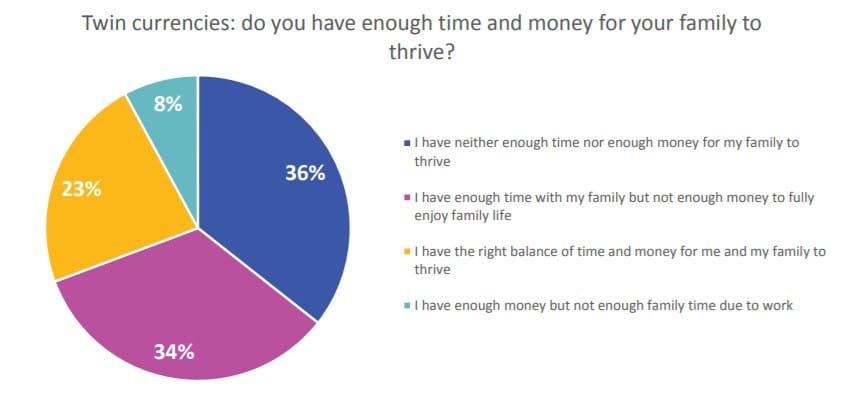

A more recent study from 2012 by Warwick university found [pdf, p17] that people with lower socioeconomic statuses were generally more likely to be time poor. Meanwhile, Working Families noted [pdf, p24] that many families feel they are both time and income poor:

Spiralling costs

As the study also noted [pdf, p6]:

According to the [JRF] in 2017, a single parent with one child (pre-school) needed to earn at least £25,900 a year before tax to achieve the minimum income standard (how much income households need to afford an acceptable standard of living). Couples with two children (requiring childcare) need to earn at least £20,400 each before tax.

It is estimated to cost £152,000 in two parent families and £183,000 in single parent families to bring up a child.

But there’s still a lack of research in this area, especially in relation to lone parents.

So what is the effect on children of parents pushed back into work?

The drive for workers

Again, little research exists. But a 2013 study by the Edinburgh Napier University noted that [pdf, p17]:

Lone parenthood is associated with lower well‐being (of lone parents and their children), but this is driven to a great extent by their relative material disadvantage.

In other words, the poorer the lone parent, the lower the well-being. Glasgow university said, with over a quarter of lone parent children living in poverty, that:

the public health impact is likely to have been considerable…

But there’s also a broader debate needed. It’s one about the societal shift from people being parents, lone or not, to being workers.

A very neoliberal coup

The DWP has slowly removed the safety net for both lone parents and families. As Gingerbread noted [pdf, p8], for example, only a decade ago lone parents would get income support to raise children until they were 16, without the pressure of being forced into work. In just ten years, the DWP reduced this age to just 3. Meanwhile, children in poverty in working households sits at around 67%.

Raising a family used to be a full-time job for one family member. But in recent decades, the shift has been towards parents working as well as bringing up children. As the Glasgow university study calls it, this “neoliberal” agenda means parents can no longer just be parents. Whatever they want, they have to prioritise working, with child rearing coming second. Partly this is because, as Netmums editor-in-chief Anne-Marie O’Leary told the Guardian:

It takes two salaries to raise a family these days. It’s not people sitting around and thinking, I fancy being a working mum. They are not doing it to buy a second home in the south of France or a sports car. They are not doing it for any highfalutin reasons, they are doing it to pay the bills and keep a roof over their heads.

The state actively encourages this, with schemes like 15 or 30 hours’ free childcare for 3- and 4-year-olds and a tax-free sum of £500 every 3 months for over-5s’ childcare. But is the question ever asked: ‘what about giving this money to parents so they can look after their child?’

Lone parents’ mental health: the thin end of the wedge?

Some parents may be happy with being able to work and raise a child; and choice is, of course, important. But is it really a fully independent choice when the system is only designed to support parents who work? Unless one partner has particularly high earnings, it’s little choice at all.

Studies are mixed [paywall] as to whether stay-at-home parenting is better or worse for a child. But we’re only in the infancy of knowing the full effect of this drive for working parents, as it is a recent phenomenon. What’s the effect of this on children’s mental health as mature adults? What effect does it have on feelings of belonging, being loved; of worth and self-esteem? And what of the parents’ attitudes to parenting and work?

The long-term effects of this societal shift may not be known for many years. But when society’s priority has shifted from people nurturing human life to being a cog in the wheel of capitalism, lone parents’ mental health may well be the thin end of the wedge.

Get Involved!

– Join The Canary so we can keep bringing you the analysis other’s miss.

Featured image via UK government – Wikimedia