We need to talk about the Turkish elections. Urgently. Because President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan may have won the presidential vote. But he didn’t win it fairly, and Turkey cannot call itself a democracy.

Even discounting the problems with the casting and counting of ballots, the campaign itself was not democratic. Kurdish MP Hişyar Özsoy – deputy chair for foreign affairs of the left-wing and pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) – told me:

We are doing this under emergency rule, where we don’t have access to media. Our chairs are in prison. So many politicians are in prison. So many people were detained… We haven’t been able to carry out a campaign. Not all candidates had equal access to the media and other opportunities that were available to the ruling party.

Elections amid destruction

I spent the day of the Turkish elections on the ground in Sur, the ancient ‘old city’ of Diyarbakır/Amed that suffered huge devastation in military assaults by the Turkish state between 2015 and 2016. Many people were killed in clashes between Turkish forces and the local Kurdish population. Before the conflict, 120,000 lived in the area. 30,000 were forced to flee, and the majority of these people have not been able to return to their homes.

Two years later, and according to Sur Platform (a local group documenting the destruction), entry to six districts in the area is still banned.

The Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal (PPT) found Turkey guilty of war crimes in May. Part of the case involved evidence of the destruction of Sur – a designated UNESCO World Heritage site. Nevin Soyukaya, the former head of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, said this was “systematic demolition and annihilation”.

“The world’s biggest jailer of media professionals”

Accompanied by lawyers and an interpreter, we visited seven schools that were acting as polling stations. I was there as an independent observer and a journalist. Aside from the first place we visited, the police prevented us from entering any of the schools. They did not accept our press passes from the International Federation of Journalists. And they also refused to accept us as independent observers.

In the second building we visited, we sat in an office with police officers who kept asking to look through lists of journalists approved by the Foreign Affairs department. Other lists they showed us were of state media journalists.

Everywhere we went, we received the same message: you’re here illegally, you were lying about your purpose, and you have a hidden agenda. But this is unsurprising given Erdoğan’s attitude towards the media. During his visit to the UK in May, he stated:

You have to make a distinction between terrorists and journalists… Are we supposed to call them journalists just because they carry credentials and ID cards?

I spoke to one journalist, who is part of Jin News – the sole women-only news network in the world. She was in prison for 15 months, and is still under investigation for her work amplifying Kurdish rights issues and women’s voices across Turkey. One part of the police investigation into her is due to her reporting on a teenager who was shot in Sur. She said:

I made news of this teenager and said the police shot him. But they don’t want people to see the crimes they’ve perpetrated on the ground and so I face an investigation.

According to Reporters Without Borders, Turkey is “the world’s biggest jailer of media professionals“.

Small problems

In Sur, the problems we encountered were small but significant. Although we were unable to enter nearly all the actual polling stations, representatives from the HDP came to speak to us. In most places, the police actively tried to listen to our conversations and openly said they wanted to record what we were saying.

Despite this, we were able to have conversations with some people more privately and they were able to give us information about what was going on.

Problems reported included representatives not being allowed to enter the buildings to monitor the ballot boxes. In each building, there were several voting rooms. HDP officials were threatened with arrest for showing people the right room to cast their vote.

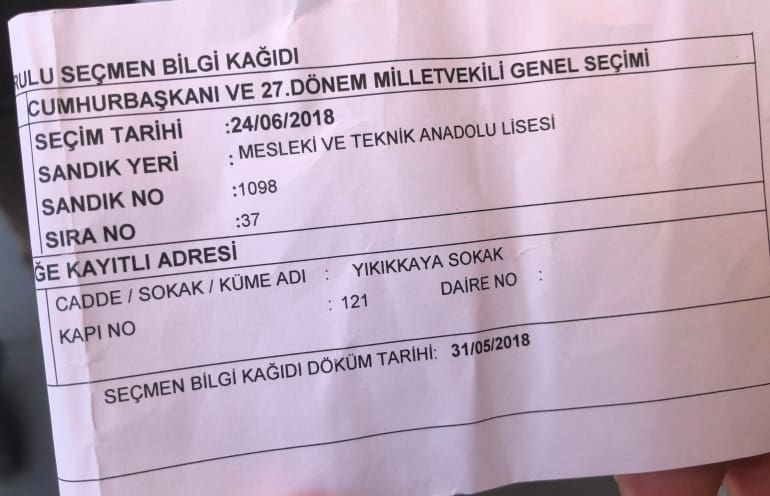

Another significant problem was for displaced people. Many of those voting in Sur were from areas that were destroyed. Their previous polling stations either no longer existed or were in banned areas. Due to this, voting papers were issued giving new voting locations. One man we spoke to showed us the paper he was sent, listing a particular school where he could vote:

But when he arrived, he was told he wasn’t registered to vote there. And no one would tell him where he could go. People we spoke to feared that hundreds of people could be affected – with worries that, once they saw their names weren’t on the list, they would go home without voting.

Big problems

The problems in Sur, however, were minor compared to reports from the rest of the country. And many people, especially in Kurdish areas, felt threatened. In Suruc, where four people were killed in the run-up to the elections, there were more threats of violence. Hişyar Özsoy stated:

They scared people, scared them on the day of elections. You saw what happened in Suruc. Yesterday, the same family was threatening people in classrooms with guns.

These tweets sum up just some of the other violence and issues people faced:

https://twitter.com/postcoupturkey/status/1010777652838400001

https://twitter.com/postcoupturkey/status/1010819823524143104

https://twitter.com/postcoupturkey/status/1010832327868641280

https://twitter.com/postcoupturkey/status/1010857210270900224

A democracy is not just about voting

Even if the elections had gone ahead without any of the above problems, Turkey has no right to call itself a democracy. A democracy is not just about being able to put a cross in a box every five years. It is about the process in which that election takes place. It’s about the laws that govern the election. And it’s about the freedoms that exist in the country as a whole.

This election took place under a “climate of fear“. And as Özsoy pointed out:

It’s not the day of elections. It’s the whole process. Over the last two years, imagine a political party where thousands of people are in prison. I mean, how do you organise people? How do you mobilise them? They have been preparing for this step-by-step.

I asked another newly elected HDP MP, Semra Güzel, whether this was a free and fair election. She replied:

Absolutely not. The whole of the state apparatus was working against us. Not to mention that we have thousands of party officials who are imprisoned. Not to mention that our presidential candidate was in prison so couldn’t engage in political activity for the elections.

Let’s stop pretending

As Özsoy stated, the HDP reaching the 10% threshold a party needs to enter parliament was “a kind of miracle” given the circumstances. But that miracle is a huge testament to the courage and determination of the Kurdish population; a population that has faced unbelievable repression and violence and yet still manages to continue surviving and fighting. All anyone I spoke to wanted was peace for the area. Yet Erdoğan labels them terrorists.

The Western media and Western politicians like to pretend that Turkey is a democracy – in large part because it has NATO’s second-largest army. But it’s time to stop pretending. It’s time to end the charade. Because there was nothing fair or free about the elections on 24 June. And Turkey has no right to call itself a democracy.

Get Involved!

– Support Peace in Kurdistan and the Kurdistan Solidarity Campaign.

Featured image via Global Panorama, screengrab and author’s own